- About 80 percent of all sugar cane in Colombia is concentrated in the Pacific coastal state of Valle del Cauca, and cane represents 50 percent of all local agricultural production.

- The Afro-Colombian population in the area surrounding the state’s capital city of Cali has seen a heavy impact on their traditional farming practices and the local environment.

- The monoculture production of cane has led to deforestation, impacting the health of local flora and fauna, according to research.

CALI, Colombia – Colombia’s Pacific coast state of Valle del Cauca, home to at least 80 percent of the country’s booming sugar cane industry, continues to rebound after excessive and damaging rains in 2011-2012. In fact, recent USDA Foreign Agricultural Services report found that the country’s cane industry continues to reach “historical averages.”

The rebound isn’t good news for everyone, though: there have long been environmental and social complications from the industry’s success.

Within Valle del Cauca, cane cultivation is a major part of the local economy. The Association of Sugar Cane Cultivators of Colombia (Asocaña) notes that over 50 percent of all local agricultural production is devoted to cane. Domestic sugar cooperative CIAMSA ranks Colombia, which also produces a variety of different kinds of sugar, among the top four most efficient cane industries in the world. The climate is suitable for year round cultivation, so Colombia grows more tons per hectare than most other nations. It is the second largest global producer of both panela (unrefined whole cane sugar) and ethanol – an alcohol fuel distilled from plant materials such as corn and sugar.

But over centuries of production, some 225,000 hectares (over 540,000 acres) in Valle del Cauca have been converted to cane. Today producers have nowhere left to expand says Arche Advisors, a U.S.-based firm that specializes in corporate responsibility. Their research shows that even industry specialists acknowledge that there are no expansion possibilities. Arche notes that investors are being urged to increase productivity in other ways, including better technology or switching to ethanol production.

Area residents have long been critical of production practices, which they say have impacted local sustainable farming practices. In interviews, these residents said that the cane industry in the Valle de Cauca has taken over entire swaths of land that were once diverse forest regions. In the area surrounding the state’s capital city of Cali, the Afro-Colombian population – already among the country’s most vulnerable – has been heavily impacted.

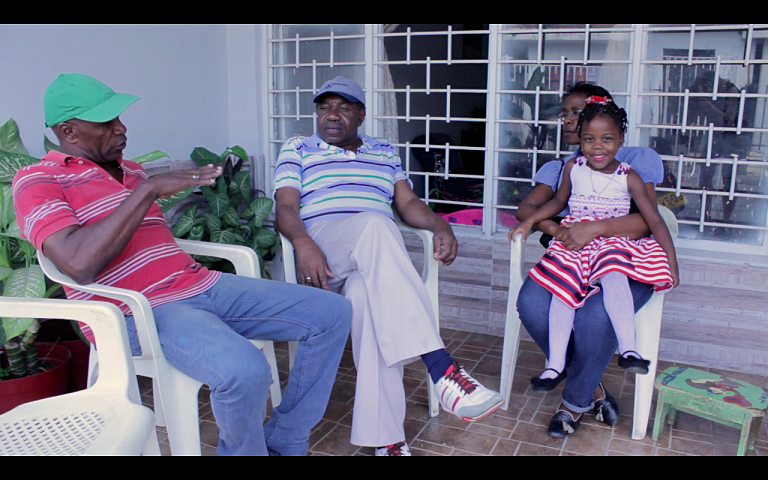

“[We] were once the owners of this area, the flat region of the Cauca Valley, which is over 220,000 hectares,” said Weimar Possu Diaz, an elderly local resident of Puerto Tejada. The town is 98 percent Afro-Colombian and just 45 minutes from Cali. “The cañeros (cane producers) came here and took the land away.”

Weimar’s sister, Darly Possu Diaz, says that area residents used to engage in more sustainable practices that were disrupted by cane growth.

“We used to have a traditional farm that was a permanent forest,” she said. “The cane has finished us here.”

Darly describes their traditional farm as a place where fruit and other staple goods such as plantains were grown, a practice still maintained by many small-holding farmers, particularly in the mountains. Darly’s farm and others like it have long provided sustenance for growers and a harvest of products such as cacao to sell at local markets.

Her memories are vivid: Darly recalls a time when she could eat various tropical fruits from local trees and watch monkeys playing close to her home. But on a 45-minute drive through the area from Cali to Puerto Tejada, all that could be seen were cane fields, with few trees in sight.

Multiple organizations note that large-scale agriculture has historically been a leading cause of deforestation in Colombia, including UK-based Earth Innovation Institute and Colombia’s Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development. Other major causes have included illicit crop cultivation (such as coca) or mining.

In the Valle del Cauca, this deforestation has happened largely through the clear cutting to make room for sugarcane.

Cane monoculture maintenance has also caused problems in the Valle del Cauca. Chemical sprays commonly used in cane cultivation (such as the herbicide glyphosate) have killed off local flora, said Irene Valez Torres, an associate professor of environmental engineering at the University of Valle in Cali, in an interview. A 2016 study by the Research Group on Orchids, Ecology and Plant Systematics at the National University of Colombia noted that glyphosate spraying near Cali’s cane fields resulted in the early death of nearby orchids.

Locals have also reported that the spraying of sugarcane fields caused permanent damage to their crops.

“When the cañeros arrived, they fumigated our crops and dried them up with the spray that they applied to the cane,” said Nancy Diaz Hidalgo from her home in Puerto Tejada. “It was too strong for our crops. That ended our traditional farms.”

The government-run Colombian Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology, and Environmental Studies (IDEAM) did not respond to numerous requests for comment. But most recently available figures from IDEAM show that deforestation in Colombia increased by 16 percent between 2013 and 2014. That puts Colombia’s 10 percent share of global biodiversity at risk under the guidelines of the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Other impacts

Researchers have long warned of the broader social impacts that deforestation and monocultures can have on local communities, including international non-profit Oxfam. The organization said in a 2014 report that monoculture expansion in general was responsible for “displacing communities, undermining smallholder livelihoods and worsening local food security.” They added that this tends to happen in already marginalized areas.

Based on Weimar’s account, that research is on par with his experience in Puerto Tejada.

“The most displaced in this country have been the black community, because unfortunately where they have been is also where natural resources have been,” he said.

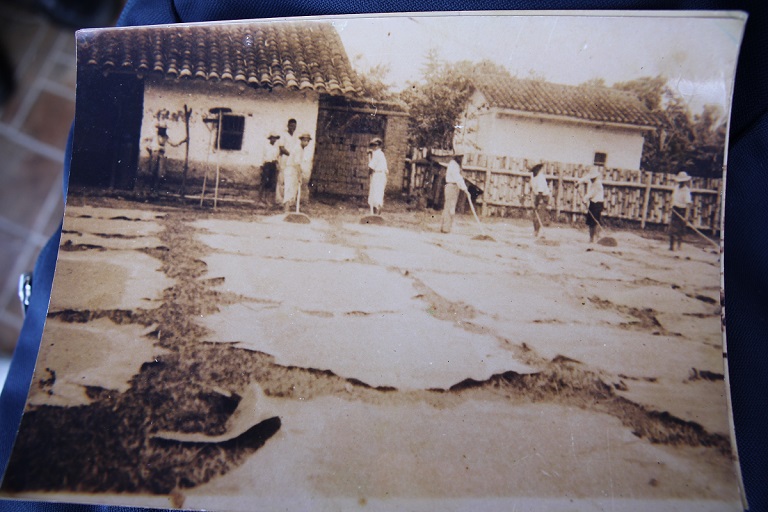

In Puerto Tejada and the region around Cali, cane cultivation expanded into territory that once belonged to Afro-Colombian communities, who had long lived off subsistence agriculture and rotational crops of coffee and cacao. The National Centre of Historical Memory notes that this was the basis of the local Afro-Colombian economy after slavery ended.

“Cacao was the base of the black economy in the north of the valley floor of the Valle del Cauca…they sold the cacao themselves, had their own resources… and worked together with their family,” Weimar said. “It was a strong economy.”

The loss of a sustainable economic base has had a lasting impact on Afro-Colombian populations, as they continue to be among the most poor and marginalized in the country. In a 2005 census report by the UNHCR, the U.N.’s refugee body, at least 15 percent of Afro-Colombians were found to have nothing to eat one or more days a week – more than twice Colombia’s national average.

“These industries took away the inheritance that our grandparents were going to leave us,” Darly said, who pointed out the vast unemployment and poverty she says she’s personally aware of among her neighbors. “These lands do not belong to the industries, these lands are our ancestors.”

Diana Nocua, a Colombian human rights worker with the National Commission of Human Rights, says that some of the most unequal states in the country are along the Pacific coast. Nocua noted that some communities in the region don’t have proper access to water, healthcare or education.

“Everything is cane fields,” Nocua said in an interview, noting that the Valle del Cauca presents specific problems vis-à-vis agriculture.“This monoculture destroyed the farmers’ own economy.”

Benefits vs. harm

The cane industry has long denied any significant negative social impacts, noting that they have brought more benefits to Colombian society than harm. That message has been echoed in local media coverage.

A 2013 article in domestic newspaper El Pais described the sector as “essential,” and noted that the area’s 20,000 sugar mills employ some 1.7 million people across the country.

“Entire communities depend on (cane) cultivation,” the article states.

In December 2016, El Pais also reported the positive effects that sugar production has had on the state’s overall economy. The article notes that sugar production, exports and construction were the top three reasons for GDP increase in the Valle del Cauca over the second half of 2016 – 3.6 percent from June to September, and 2.3 percent from October to December. These numbers are also well above national growth, which only saw a 1.2 percent rise in GDP in the third trimester of 2016.

Ethanol

In recent years, Colombia’s cane industry has grown in response to the push to increase ethanol production, which the government is looking to as a first step in breaking its dependence on fossil fuels.

This expansion has been aided by government incentives, including a 2001 law mandating that gasoline must be mixed with 8-10 percent (depending on the state) biofuel. The former conservative administration of Alvaro Uribe that ended in 2010 also championed the ethanol industry and incentivized it through tax exemptions, special loans and increased access to land for ethanol producers.

But several international research and advocacy organizations say that it’s questionable whether ethanol — and the cane industry at large — can really be considered sustainable.

Cane production requires an immense amount of water. During a typical growing period, sugar cane needs anywhere from roughly 59-98 inches (1500-2500 mm) of water, more than any other crop, according to the U.N.’s Food and Agricultural Organization. In contrast, crops like barley, oats and wheat only require 17-26 inches (450-650 mm) of water in a growing period. Secondly, studies by Oxfam, the UN, and the Washington Office on Latin America note that the ethanol industry has been accused of violating labor rights. Oxfam also points to what they consider to be inadequate labor regulations.

But based on information published by Asocaña, which represents Colombia’s sugar sector both nationally and internationally, damage to the environment is an exception and not a rule of the cane industry.

Asocaña did not respond to inquiries for comment for this story, but the organization is one of several in the biofuel sector that have pledged to expand cane production without causing further deforestation. They also say they’ve developed programs to reverse some of the damage already done.

In a 2012 annual review, Asocaña reported that between Dec. of 2011 and Dec. of 2012 alone, over 3,225 hectares of land benefited from their “reforestation, conservation and protection” projects. This happened even with a 15.7 percent increase in ethanol production in the same time period, the report states.

Environmental policies

The current administration of Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos recently implemented key strategies to tackle deforestation under the umbrella of plans for addressing the country’s high carbon emissions. These include the Colombian Strategy for Low-Carbon Development and a plan to achieve zero deforestation in the Amazon by 2020, according to the Global Canopy Programme’s REDD desk.

But Santos has also made it clear that expanding the country’s agricultural sector, including the biofuels industry, is crucial to national development plans, which could contradict environmental protectionist policies.

Area residents like Darly, as well as international organizations such as The Earth Institute, remain hopeful that the recent peace agreement signed between the FARC and the government will be the first step in addressing environmental and social concerns, since one of its main clauses is to invest in rural development issues.

However, the current government policy of agricultural expansion and support for the cane industry could make changes in this business hard to achieve.

Banner image: Flooded sugar cane fields near Colombia’s third largest city, Cali, in the department of Valle Del Cauca, during an intense rainy season. Photo by Neil Palmer (CIAT)

Kimberley Brown is a freelance journalist based in South America. You can find her on Twitter at @KimberleyJBrown.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Citations:

Perea-Morera, E. and Otero, J.T. Effect of Herbicide Glyphosate in Endophite Root and Orchids. University of Costa Rica. 2016.

Barry D., Bailis, Robert (Eds.). Sustainable Development of Biofuels in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2014. Springer Science Business+Media.

Background on sugarcane, UN Food and Agriculture Organization

Crop water needs, UN Food and Agriculture Organization

Drivers of Deforestation in Colombia, Earth Innovation Institute

Deforestation in Colombia, 2014, IDEAM

Colombia Sugar Industry Situational Analysis, Arche Advisers

UNHCR 2005 census

Smallholders at Risk. Oxfam briefing paper, 2014.

Workers Without Rights, 2010. Washington Office on Latin America