World Growth International, a group that advocates on behalf of industrial forestry interests, has criticized Golden Agri Resources (GAR), Indonesia’s largest palm oil producer, for signing a forest policy that aims to protect high conservation value and high carbon stock forest and requires free, prior informed consent (FPIC) in working with communities potentially affected by oil palm development.

In a newsletter published March 10, World Growth International claimed that GAR’s agreement “could severely hamper the company’s growth” by limiting where it can establish new plantations and says that negotiating with multiple stakeholders “will delay and complicate any investment by the company.” World Growth International concludes by implying that GAR may renege on its commitment.

But Peter Heng, Managing Director, Communications and Sustainability at GAR, disagreed with World Growth International’s assessment.

“At this point, the additional cost of this policy will not be material,” he told mongabay.com in response to World Growth International’s mailing. “Based on initial field work, we think that the land to be earmarked as high carbon stock is not significant as GAR’s concessions are on degraded land.”

“What is important is the positive impact that the Forest Conservation Policy will have on conserving the forests, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity loss and improving the livelihoods of people.”

The rebuke from GAR is notable because Alan Oxley, who heads World Growth International, along with the Australia-based marketing firm ITS Global, was paid last year by the Sinar Mas group, which controls GAR, to cast doubt on environmental complaints lodged by Greenpeace, which had been campaigning against GAR’s subsidiary PT Sinar Mas Agro Resources & Technology (PT SMART). Heng told mongabay.com that GAR is not engaging Oxley.

The newsletter from World Growth International also made other questionable claims. It said “palm plantations are generally not suited to peat lands”, when in fact more than a million hectares of oil palm plantations have been planted on peatlands in Indonesia and Malaysia. Indeed peatlands are often targeted by companies because of low cost of land acquisition due to fewer competing claims from local communities. Furthermore, palm oil yields on peat soils can be competitive with mineral soils provided plantations are developed carefully and water levels are well-managed.

World Growth also asserted that “in the NGO world FPIC generally only refers to indigenous peoples rather than local communities.” Yet recent complaints over FPIC to the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil have revolved around local communities in Indonesian Borneo, not indigenous groups. For example, a complaint resolved last week was filed on behalf of a community—not a forest tribe—in West Kalimantan. Under the agreement, PT Agro Wiratama, a subsidiary of the Musim Mas group, will return 1,000 hectares of its 9,000 hectare concession to the community.

But World Growth International’s dubious claims are nothing new. The group, which portrays itself as a humanitarian organization, yet consistently pushes policies that favor industrial forestry interests over communities, has falsely claimed that oil palm plantations sequester more carbon than rainforests and that the leading cause of deforestation in Asia is subsistence agriculture, rather than enterprise-driven activities. In two of its reports, World Growth International misattributed views to Frances Seymour, the Director General of CIFOR, a forest policy research institution. World Growth International said Seymour, when speaking at a U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization event in 2009, blamed subsistence farmers for most deforestation, but a review of the transcript from her talk does not support this interpretation. Speaking with mongabay.com, Seymour flatly denied the notion that the poor are primarily to blame for deforestation today.

World Growth International reports have also dismissed other important environmental concerns, including emissions from conversion of peatlands for plantations and loss of habitat for threatened species including orangutans and Sumatran tigers.

Its positions—and conduct—have produced many critics. In December 2010, Agus Purnomo, Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s special assistant on climate change, said Oxley was misrepresenting the objectives of Indonesia’s proposed moratorium on new concessions in primary forest areas and peatlands. Last November, the group run by Wangari Maathai, the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize winner for her tree-planting campaign in Africa, blasted World Growth International’s Oxley for using her name to imply that she supports the large-scale conversion of tropical forests for industrial plantations. And in October, a group of prominent scientists castigated Oxley. In an open letter the scientists identify World Growth International and ITS Global as front groups for the palm oil, timber, and wood-pulp industries.

“A number of the key arguments of World Growth International, ITS Global, and Alan Oxley, represent significant distortions, misrepresentations, or misinterpretations of fact,” wrote the scientists, led by William F. Laurance, a researcher at James Cook University.

“In other cases, the arguments they have presented amount to a ‘muddying of the waters’ which we argue is designed to defend the credibility of the corporations we believe are directly or indirectly supporting them financially. As such, World Growth International and ITS Global should be treated as lobbying or advocacy groups, not as independent think-tanks, and their arguments weighted accordingly.”

Yet the complaints haven’t stopped World Growth International, which continues to send out its email newsletter and publish reports that criticize environmental groups, scientists, and now, in a new twist, palm oil companies working to reducing their impact on forests.

World Growth International did not reply to several requests for comment from mongabay.com.

Related articles

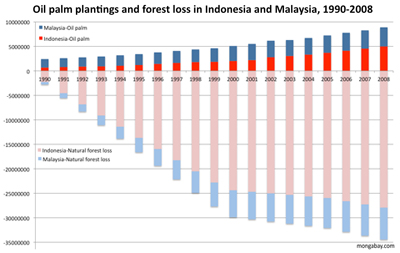

First large-scale map of oil palm plantations reveals big environmental toll

(03/07/2011) Expansion of industrial oil palm plantations across Malaysia and Indonesia have laid waste to vast areas of forest and peatlands, exacerbating greenhouse gas emissions and putting biodiversity at risk, reports a new satellite-based analysis that maps mature oil palm estates across Peninsular Malaysia, Borneo, and Sumatra.

Breakthrough? Controversial palm oil company signs rainforest pact

(02/09/2011) One of the world’s highest profile and most controversial palm oil companies, Golden Agri-Resources Limited (GAR), has signed an agreement committing it to protect tropical forests and peatlands in Indonesia. The deal—signed with The Forest Trust, an environmental group that works with companies to improve their supply chains—could have significant ramifications for how palm oil is produced in the country, which is the world’s largest producer of palm oil.

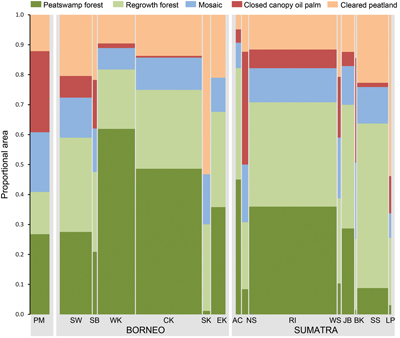

Malaysian palm oil producers destroying Borneo peat forests faster than ever before

(02/01/2011) Peatlands and rainforests in Malaysia’s Sarawak state on the island of Borneo are being rapidly destroyed for oil palm plantations, according to new studies by environmental group Wetlands International and remote sensing institute Sarvision. The analysis shows that more than one third (353,000 hectares or 872,000 acres) of Sarawak’s peatswamp forests and ten percent of the state’s rainforests were cleared between 2005 and 2010. About 65 percent of the area was converted for oil palm, which is replacing logging as timber stocks have been exhausted by unsustainable harvesting practices.

Greening the world with palm oil?

(01/26/2011) The commercial shows a typical office setting. A worker sits drearily at a desk, shredding papers and watching minutes tick by on the clock. When his break comes, he takes out a Nestle KitKat bar. As he tears into the package, the viewer, but not the office worker, notices something is amiss—what should be chocolate has been replaced by the dark hairy finger of an orangutan. With the jarring crunch of teeth breaking through bone, the worker bites into the “bar.” Drops of blood fall on the keyboard and run down his face. His officemates stare, horrified. The advertisement cuts to a solitary tree standing amid a deforested landscape. A chainsaw whines. The message: Palm oil—an ingredient in many Nestle products—is killing orangutans by destroying their habitat, the rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra.

Indonesian climate official: palm oil lobbyist is misleading the public

(12/29/2010) Alan Oxley, a lobbyist for industrial forestry companies in the palm oil and pulp and paper sectors, is deliberately misleading the public on deforestation and associated greenhouse gas emissions, said a top Indonesian climate official.

Logging, palm oil giant hires U.S. ambassador as lobbyist

(12/09/2010) Sinar Mas Group, the sprawling Indonesian conglomerate that has interests in coal mining, logging and wood-pulp production, palm oil plantations, real estate, and other industries, has hired Cameron Hume, the former U.S. ambassador to Indonesia, as an adviser, according to Detik.com. Ambassador Hume stepped down from his post at the embassy in August.

Nobel Prize winner, anti-poverty group, scientists fire back at logging lobbyist

(11/01/2010) An industrial lobbyist is facing mounting criticism for his campaign to reduce social and environmental safeguards in Indonesia.

Scientists blast greenwashing by front groups

(10/27/2010) A group of prominent scientists has published an open letter challenging the objectivity of World Growth International, an NGO that claims to operate on behalf of the world’s poor, and its leader Alan Oxley, a former trade diplomat who also chairs ITS Global, a marketing firm. The letter, published online in several forums, slams World Growth and ITS Global as a front groups for forestry companies. The scientists note that while the groups have not disclosed their sources of funding, they assert ITS receives funding from Sinar Mas, an Indonesian conglomerate that controls Asia Pulp & Paper (APP), a forest products brand, and Sinar Mas Agro Resources & Technology, a palm oil firm, among other companies.

Misleading claims from a palm oil lobbyist

(10/23/2010) In an editorial published October 9th in the New Straits Times (“Why does World Bank hate palm oil?”), Alan Oxley, a former Australian diplomat who now serves as a lobbyist for logging and plantation companies, makes erroneous claims in his case against the World Bank and the International Finance Corp (IFC) for establishing stronger social and environmental criteria for lending to palm oil companies. It is important to put Mr. Oxley’s editorial in the context of his broader efforts to reduce protections for rural communities and the environment.

Corporations, conservation, and the green movement

(10/21/2010) The image of rainforests being torn down by giant bulldozers, felled by chainsaw-wielding loggers, and torched by large-scale developers has never been more poignant. Corporations have today replaced small-scale farmers as the prime drivers of deforestation, a shift that has critical implications for conservation. Until recently deforestation has been driven mostly by poverty—poor people in developing countries clearing forests or depleting other natural resources as they struggle to feed their families. Government policies in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s had a multiplier effect, subsidizing agricultural expansion through low-interest loans, infrastructure projects, and ambitious colonization schemes, especially in the Amazon and Indonesia. But over the past two decades, this has changed in many countries due to rural depopulation, a decline in state-sponsored development projects, the rise of globalized financial markets, and a worldwide commodity boom. Deforestation, overfishing, and other forms of environmental degradation are now primarily the result of corporations feeding demand from international consumers. While industrial actors exploit resources more efficiently and cause widespread environmental damage, they also are more sensitive to pressure from consumers and environmental groups. Thus in recent years, it has become easier—and more ethical—for green groups to go after corporations than after poor farmers.