This letter was submitted to The New Straits Times a week ago in response to an editorial penned by Alan Oxley. The New Straits Times has not published the letter as of this time, therefore it is being posted on mongabay.com.

In an editorial published October 9th in the New Straits Times (“Why does World Bank hate palm oil?“), Alan Oxley, a former Australian diplomat who now serves as a lobbyist for logging and plantation companies, makes erroneous claims in his case against the World Bank and the International Finance Corp (IFC) for establishing stronger social and environmental criteria for lending to palm oil companies. It is important to put Mr. Oxley’s editorial in the context of his broader efforts to reduce protections for rural communities and the environment.

In his editorial, Oxley mischaracterizes the IFC’s audit process; confuses World Bank’s policy-making bodies; and cites the wrong group leading the complaints to the IFC. Oxley portrays the Bank’s multistakeholder process for devising a strategy to resume lending to palm oil companies as elevating “the green interests, mostly based in wealthy countries, over the bank’s core mission of reducing poverty” when in fact the majority of those signing on to the complaints and inputs to the World Bank are local indigenous peoples, smallholders groups and national non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Forest clearing for oil palm in Central Sarawak.

|

Oxley claims to campaign on behalf of ending poverty, yet the World Bank issue centers around the land rights of poor rural communities being violated by a large palm oil company. If Oxley is sincere about the plight of the poor, why is he siding with some of the world’s most criticized logging and plantation companies?

The answer is simple, Oxley’s “anti-poverty” platform is little more than campaign on behalf of big forestry companies to reduce regulation, including social and environmental protections, in an industry that has demonstrated a need for safeguards (e.g. this month’s Rajang logjam). While many companies–including Wilmar, which is at the center of the IFC complaint–are moving toward more responsible policies that better ensure the long-term viability of their industry and the health of the environment, there remain holdouts that would rather mislead the public than substantively improve operations. That’s where Mr. Oxley comes in with his Washington D.C.-based World Growth International and his marketing firm ITS Global.

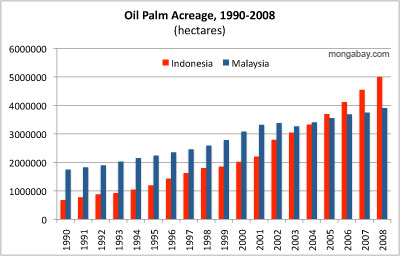

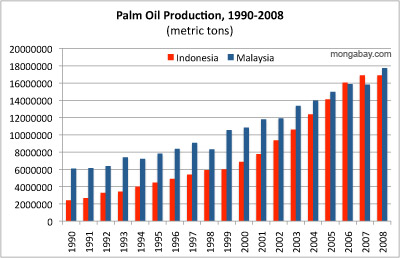

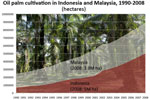

Expansion of palm oil production has generated considerable income in Malaysia and Indonesia, but in some places has exacerbated social conflict. |

Oxley is quick to attack anyone who criticizes any of his corporate clients as rabid environmentalists with an anti-development agenda. Lately he’s been particularly active on behalf of Sinar Mas holding companies, which have been under pressure from NGOs for conflict with communities and deforestation in Sumatra and Kalimantan. In this effort, Oxley has recently published several press releases, reports (sometimes presented as “independent” audits), and editorials that contain distortion and outright corruption of fact. Oxley had made false claims about the underlying drivers of deforestation, the environmental performance of palm oil, the groups that are working to improve the well-being of the rural poor, and commodity-certification initiatives. He has even used language to imply that Wangari Maathai, the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize winner for her tree-planting campaign in Africa, supports the large-scale conversion of tropical forests for industrial plantations. Maathai has not voiced support for such activities, which are against the spirit of her community-based Greenbelt Movement, and does not support World Growth International.

These distortions and misrepresentations undermine the long-term health and goodwill of the very industries that are paying Oxley. These corporations can have a central role in the wise use and stewardship of natural resources and it is a shame Mr. Oxley attempts to obstruct this positive role through his campaign.

Related articles

Corporations, conservation, and the green movement

(10/21/2010) The image of rainforests being torn down by giant bulldozers, felled by chainsaw-wielding loggers, and torched by large-scale developers has never been more poignant. Corporations have today replaced small-scale farmers as the prime drivers of deforestation, a shift that has critical implications for conservation. Until recently deforestation has been driven mostly by poverty—poor people in developing countries clearing forests or depleting other natural resources as they struggle to feed their families. Government policies in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s had a multiplier effect, subsidizing agricultural expansion through low-interest loans, infrastructure projects, and ambitious colonization schemes, especially in the Amazon and Indonesia. But over the past two decades, this has changed in many countries due to rural depopulation, a decline in state-sponsored development projects, the rise of globalized financial markets, and a worldwide commodity boom. Deforestation, overfishing, and other forms of environmental degradation are now primarily the result of corporations feeding demand from international consumers. While industrial actors exploit resources more efficiently and cause widespread environmental damage, they also are more sensitive to pressure from consumers and environmental groups. Thus in recent years, it has become easier—and more ethical—for green groups to go after corporations than after poor farmers.

Malaysia/Indonesia partnership proposed to counter environmental complaints over palm oil

(10/18/2010) Malaysia and Indonesia should establish “a joint council based in Europe and the United States” to boost the image of palm oil and counter criticism from environmental and human rights groups, a Malaysian minister told Malaysia state press.

The Nestlé example: how responsible companies could end deforestation

(10/06/2010) The NGO, The Forest Trust (TFT), made international headlines this year after food giant Nestlé chose them to monitor their sustainability efforts. Nestlé’s move followed a Greenpeace campaign that blew-up into a blistering free-for-all on social media sites. For months Nestle was dogged online not just for sourcing palm oil connected to deforestation in Southeast Asia—the focus of Greenpeace’s campaign—but for a litany of perceived social and environmental abuses and Nestlé’s reactions, which veered from draconian to clumsy to stonily silent. The announcement on May 17th that Nestlé was bending to demands to rid its products of deforestation quickly quelled the storm. Behind the scenes, Nestlé and TFT had been meeting for a number of weeks before the partnership was made official. But can TFT ensure consumers that Nestlé is truly moving forward on cutting deforestation from all of its products?

Compliance with national law not enough to meet int’l market demands

(10/05/2010) A UK-based cosmetics firm is severing ties with its palm oil supplier after a story in The Observer reported the Colombia-based company sought the eviction of peasant farmer families to develop a new oil palm plantation, reports the Guardian.

80% of tropical agricultural expansion between 1980-2000 came at expense of forests

(09/02/2010) More than 80 percent of agricultural expansion in the tropics between 1980 and 2000 came at the expense of forests, reports research published last week in the early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The study, based on analysis satellite images collected by the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and led by Holly Gibbs of Stanford University, found that 55 percent of new agricultural land came at the expense of intact forests, while 28 percent came from disturbed forests. Another six percent came from shrub lands.

Rapid growth of palm oil industry tramples indigenous peoples’ rights, says report

(08/30/2010) Rapid expansion of oil palm plantations across Southeast Asia have run roughshod over customary tenure systems, resulting in exploitation of local communities, conflict, and outright human rights abuses, reports a new assessment of the palm oil sector by the Forest Peoples Programme (FPP), an international indigenous rights group.

Brazil launches major push for sustainable palm oil in the Amazon

(05/07/2010) Brazilian President Lula da Silva on Thursday laid out plans to expand palm oil production in the Amazon while minimizing risk to Earth’s largest rainforest. The plan, called the Program for Sustainable Production of Palm Oil (O Programa de Produção Sustentável de Óleo de Palma), will provide $60 million to promote cultivation of oil palm in abandoned and degraded agricultural areas, including long-ago deforested lands used for sugar cane and pasture. Brazilian officials claim up to 50 million hectares of such land exist in the country.