The rise of industrial deforestation and its implications for conservation.

The image of rainforests being torn down by giant bulldozers, felled by chainsaw-wielding loggers, and torched by large-scale developers has never been more poignant. Corporations have today replaced small-scale farmers as the prime drivers of deforestation, a shift that has critical implications for conservation.

Until recently deforestation has been driven mostly by poverty—poor people in developing countries clearing forests or depleting other natural resources as they struggle to feed their families. Government policies in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s had a multiplier effect, subsidizing agricultural expansion through low-interest loans, infrastructure projects, and ambitious colonization schemes, especially in the Amazon and Indonesia. But over the past two decades, this has changed in many countries due to rural depopulation, a decline in state-sponsored development projects, the rise of globalized financial markets, and a worldwide commodity boom. Deforestation, overfishing, and other forms of environmental degradation are now primarily the result of corporations feeding demand from international consumers. While industrial actors exploit resources more efficiently and cause widespread environmental damage, they also are more sensitive to pressure from consumers and environmental groups. Thus in recent years, it has become easier—and more ethical—for green groups to go after corporations than after poor farmers.

As counter-intuitive as it may seem, corporate consolidation—a trend since the 1990s—is also making it easier for green groups to go after companies. As Jason Clay, Senior Vice President of Market Transformation at WWF, noted in his July TED talk in Oxford, convincing leading companies to change the way they source commodities can have a substantial impact on global supply chains.

“100 companies control 25 percent of the trade of all 15 of the most significant commodities on the planet,” he said. “We can get our arms around 100 companies.”

“If these companies demand sustainable products, they’ll pull 40-50 percent of production. Companies can push producers faster than consumers can.”

But who pushes companies? Surprising as it may seem, environmental activists are having an out-sized role in changing corporate behavior.

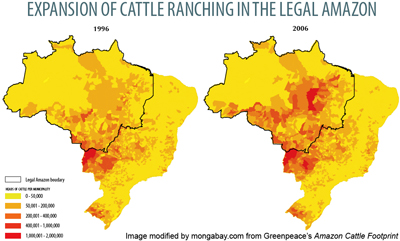

For example, during the summer of 2009 Greenpeace released a report linking deforestation in the Amazon to major consumer products including fast-food hamburgers, Gucci handbags, and Nike shoes. The fallout was immediate—Brazil’s cattle industry, which is the largest in the world and a dominant force in Brazilian politics—was brought to a standstill virtually overnight. Brazilian cattle giants saw their offices raided and loans suspended or revoked. They also faced stepped-up threats from the government—led by the public prosecutor of the state of Pará—and a sharp public rebuke from some of their biggest buyers including Walmart, Nike, and Timberland, who demanded greater accountability for their supply chains. Under pressure from their customers and the government, Brazilian cattle processors and traders fell into line, declaring new sourcing policies and moratoriums on deforestation. The hottest commodity in the Brazilian Amazon became credible supply-chain management, spawning a rush to develop certification systems and land registries for “responsible” ranches.

“The industry—from Nike and Adidas to the slaughter plants—is under pressure to have a clean supply chain,” said John Carter, a rancher who runs Alianca da Terra, a Brazilian NGO that is developing a land registry to support a certification system for the cattle industry. “Greenpeace essentially created a federal mandate that everyone had to come into compliance via a land registry.”

“Greenpeace changed the game. Environmental stewardship will become the standard of production once the economic incentives of certification—like low-interest loans and access to image-conscious buyers—are in place.”

The push for reform is being led by big buyers. Walmart Brazil, the largest beef buyer in the country, and Grupo Pão de Açúcar, a big supermarket chain, have set up the first traceability system for beef, allowing customers with a cell phone or an Internet connection to track packaged meat back to its ranch of origin. Both companies plan to extend traceability to other timber and soy sourced from the Amazon to ensure that the production of these commodities doesn’t come at the expense of rainforests.

Oil palm plantation adjacent to tropical rainforest. |

But it’s not only the Amazon cattle industry that has been shocked into action by activist campaigns. Unilever, a consumer-products conglomerate that is the world’s largest corporate buyer of palm oil, was caught up in a scandal in 2008 when Greenpeace claimed the company’s supplier—ostensibly a “responsible” palm oil producer—was involved in forest destruction in Borneo. Hiring an independent investigator, Unilever learned that the palm oil supplier, Sinar Mas Agro Resources and Technology (SMART), was indeed clearing rainforests and carbon-dense peatlands. In December 2009 Unilever suspended buying from the company. Since then, Nestle, Kraft, Burger King, and General Mills have followed suit. Cargill, America’s largest palm oil importer, is now pressuring SMART’s parent company, Golden Agri Resources, to clean up its operations.

Another potent example comes from Madagascar, a treasure trove of biodiversity in the Indian Ocean. In the aftermath of a military coup more than a year ago, Madagascar’s rainforest parks have been besieged by illegal loggers targeting valuable rosewood and other hardwoods. The timber is usually transported by international carriers to Reunion and Mauritius, and then on to China where it is turned into furniture for export. Some of the wood ends up in Europe and the United States. Madagascar’s coup leaders are apparently complicit in the lucrative trade, making it difficult to address the issue on the ground. So the pressure point for rosewood trafficking—at least in the short term—is the foreign shipping companies. Confronted by tour operators whose business depends on national parks and wildlife, three companies immediately stopped trafficking in rosewood.

Rosewood logs in Madagascar. |

However Delmas, a French company, continued carrying rosewood for months, making it a clear target for environmentalists. When word leaked about an impending shipment scheduled for late December, Forests.org, a web-based activist group run by Glen Barry, seized on the opportunity, bombarding the company and the French government with thousands of messages arguing that Delmas was undermining France’s negotiating position and facilitating the destruction of Madagascar’s national parks. The French government was included because it had taken a strong forest conservation position during climate talks in Copenhagen.

The campaign proved too much for Delmas, and a major rosewood shipment—worth $20-80 million to traders—was canceled. A few weeks later it emerged that Delmas had quit the rosewood business despite direct threats from coup leaders that it would be blacklisted if it didn’t resume the trade. A Delmas representative said it wasn’t worth the damage to the firm’s reputation to transport the illegally logged timber.

“It’s really impressive that environmental activists have influenced a major corporation such as Delmas,” said Dr. William Laurance, a researcher at James Cook University in Australia, who has analyzed the transition from poverty-driven to enterprise-driven deforestation. “Many corporations are learning that it’s bad business to engage in environmentally poor practices. Kudos to Delmas for changing their tack, and to Glen Barry and his colleagues for focusing attention on this critical issue.”

But while the campaign achieved its short-term objective of blocking the rosewood shipments, the subsequent response from traders reflects the difficulties of going after corporate transgressors. For example, after a consumer in Germany complained to authorities that Theodor Nagel, a major tropical timber importer based in Germany, was advertising “Madagascar rosewood” on its web site, the company replaced “Madagascar” with “Brazilian.” Furthermore, traders in Madagascar are reported to be looking now for more discreet ways to ship rosewood. They may be helped eventually by Chinese freighters, whose owners have fewer qualms about international criticism.

Theodor Nagel’s relabeling is but one example of how companies can counteract environmental campaigns. Greenwashing—or misrepresenting the environmental qualities of a product—is another common strategy.

“Every company engaged in damaging enterprises is likely to have a fancy Internet smokescreen of Flash-media PR about the environment and uplifting the world’s poor,” said Rowan Moore Gerety, a journalist who reports on sustainability issues. “This is sold to us (the consumers) as transparency about the project, when in fact we have no information about its core, which is really a question of chemistry, economics, and trade.“

Greenpeace activists unfurl a giant banner “APP-Stop destroying Tiger Forests” in its campaign against Asia Pulp & Paper (APP). The banner was deployed in an area of active clearing by PT. Tebo Multi Agro (TMA), an affiliate of APP, on the southern part of the Bukit Tigapuluh landscape. Photo courtesy of Greenpeace. |

A prime example can be found in Sinar Mas Group, the conglomerate that controls SMART, and Asia Pulp & Paper (APP), a paper products brand that sources from several Indonesian companies and has long been targeted by green groups for its poor environmental record. Campaigns led by the Rainforest Action Network, Forest Ethics, Greenpeace, and WWF (a former partner), among others, led some of APP’s most prominent buyers—among them Staples, Office Depot, Walmart, Woolworth, and Gucci Group—to cancel contracts with the company. In addition, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the green standard for forest products, prevented APP from using its eco-label on its products. To stem the loss of customers, APP has embarked on a campaign to rebrand itself as a leader on sustainability. Its new web site features bird sounds and verdant forests while proclaiming its support for “economic, social, and environment sustainability.” The company also is running ads on CNN touting its green credentials.

APP maintains it operates within Indonesian law and is interested in the long-term sustainability of its operations. The company has also moved to protect some forest areas, announcing this month that it would set aside more than 15,000 hectares of Sumatran peat forest in a carbon conservation project, which it says will benefit local people.

“We are committed to the protection of high conservation value forests and critical peatlands, but forest sustainability in Indonesia relies heavily on sustainable communities as well,” said Ian Lifshitz, Sustainability & Public Outreach Manager at APP. “We’re fortunate that community development is a product of that business and we do in fact view creating community opportunity as part of our mission. Carbon forest is one new option we can use with set-aside areas within our affiliates’ concession lands that merit conservation.”

“This program was developed as means to provide more sustainable income for the indigenous community through the establishment of jobs for locals, [establishment of] eco tourism… [and] helping to develop eco-tourism or micro-financing.,” he said of the carbon project. “Our goal is to use this as a pilot program and continue to make an investment in other local communities in the future.”

|

|

But while APP’s carbon project and messaging suggest a greener company with friendlier community relations, its hiring of a notorious lobbyist indicates the firm is still investing in another approach to dealing with criticism: greenwashing. APP and Sinar Mas have retained the services of Alan Oxley, a former Australian diplomat, who specializes in managing the images of forestry companies, including one of the most controversial logging companies in the world, Rimbunan Hijau, which environmentalists have long singled out for its damaging operations in Papua New Guinea, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Through his new NGO, World Growth International, and his consultancy, ITS Global, Oxley issues reports and press releases containing dubious claims about the underlying drivers of deforestation, the groups that are working to improve the well-being of the rural poor, and commodity-certification initiatives. Oxley has even used language to imply that Wangari Maathai, the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize winner for her tree-planting campaign in Africa, supports the large-scale conversion of tropical forests for industrial plantations. Maathai has not voiced support for such activities, which are against the spirit of her community-based Greenbelt Movement, and she has communicated that she does not support World Growth International.

“Maathai emphatically does not support Oxley’s assertion,” said Francesca de Gasparis, Director of Green Belt Movement International.

Oxley’s campaign has lately been parroted by a new U.S. group, the Consumer Alliance for Global Prosperity (CAGP). CAGP alleges “collusion” against Asian forestry companies among environmentalists, companies that have implemented eco-sourcing criteria for paper products (many of which are companies APP has lost as clients), and trade unions. CAGP denies any affiliation with World Growth International, yet uses the same mailing list (as does a new Nigeria-based think tank, the Initiative for Public Policy Analysis).

Oxley’s campaigning extends into palm oil, which has seen its share of greenwashing, much to the detriment of responsible producers who have been tarnished by the conduct of a few bad actors. For all the virtues of palm oil as the world’s highest-yielding source of vegetable oil, expansion over the past 25 years has consumed vast tracts of forest across Indonesia and Malaysia. Analysis of remote-sensing data suggests that more than half the expansion since 1990 has occurred at the expense of natural forests. But instead of acknowledging this and addressing concerns head on, marketing bodies for the industry have tended to expend efforts on denial and greenwashing—efforts seemingly modeled after the tactics employed by the fossil fuel industry in the United States. The integrated marketing campaign includes web sites, blogs, think tanks, editorials, and advertisements. But the message conveyed has at times brought unwanted attention: placements have twice been banned for false claims by Britain’s Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), a group that regulates advertising. One video placement used iguanas and hummingbirds — species found nowhere near Malaysia—to suggest that biodiversity thrives in plantations despite a large body of scientific studies showing that oil palm estates are biologically impoverished compared even with heavily logged forests. Dr. Yusof Basiron, CEO of the Malaysian Palm Oil Council, the government-backed marketing arm of the Malaysian palm oil industry, has gone so far as to claim that endangered orangutans benefit from living in proximity to oil palm plantations. Environmentalists scoff at the notion, maintaining that oil palm expansion is one of the greatest threats to orangutans.

Deforestation in Peru |

The efforts illustrate the extent to which companies will work to mislead consumers. However, some members of industry realize that it will take more than deception to alleviate environmental concerns and are working to improve environmental performance through certification schemes that set standards for production and distribution. But these are dependent on consumer sophistication—an ability to distinguish between “good” and “bad” palm oil and timber, rather that making blanket conclusions about an entire commodity, and preference for “greener” products. In some markets—notably India and China but even the United States and Europe in some cases — there is little willingness among consumers to pay a premium for eco-friendly goods. So while some palm oil producers have thrown their weight behind a certification scheme devised by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), demand for certified sustainable palm oil has been slow to materialize. Until demand picked up in recent months, environmental groups like WWF—which supported RSPO—were under pressure to show producers that it is worth their while to bear the additional costs of greener palm oil. Consumer apathy could thus prove to be the biggest threat to greening the supply chain, and activist groups may increasingly find themselves having to call attention to companies that adopt environmentally friendly approaches to business.

But at the same time, environmental groups need to beware of overzealousness in their campaigns. Misrepresenting the evils of corporations or exaggerating the severity of environmental problems—conduct termed “blackwashing”—can risk undermining public confidence and support, doing long-term damage to their cause. Greenpeace, for one, has been criticized for championing theatrics over facts. But recent examples in Southeast Asia and Brazil show that when activist groups gets the facts right, and these resonate with consumers, the efforts can have a profound impact. Last summer’s Greenpeace report is a big reason why the Brazilian cattle industry may now be on the cusp of transitioning from being the world’s largest single driver of deforestation to a critical component in helping slow climate change.

Related articles

Walmart takes on Amazon deforestation

(10/18/2010) The world’s largest retailer last week announced new sourcing criteria for commodities closely associated with deforestation: palm oil and beef from the Amazon.

Environmentalists must recognize ‘biases and delusions’ to succeed

(10/18/2010) As nations from around the world meet at the Convention on Biological Diversity in Nagoya, Japan to discuss ways to stem the loss of biodiversity worldwide, two prominent researchers argue that conservationists need to consider paradigm shifts if biodiversity is to be preserved, especially in developing countries. Writing in the journal Biotropica, Douglas Sheil and Erik Meijaard argue that some of conservationists’ most deeply held beliefs are actually hurting the cause.

Malaysia/Indonesia partnership proposed to counter environmental complaints over palm oil

(10/18/2010) Malaysia and Indonesia should establish “a joint council based in Europe and the United States” to boost the image of palm oil and counter criticism from environmental and human rights groups, a Malaysian minister told Malaysia state press.

Asia Pulp & Paper fumbles response to deforestation allegations by Greenpeace

(09/28/2010) A new audit that seems to exonerate Asia Pulp & Paper from damaging logging practices in Indonesia was in fact conducted by the same people that are running its PR efforts, raising questions about the much maligned company’s commitment to cleaning up its operations. The audit slams Greenpeace, the activist group that accused Asia Pulp & Paper (APP) of illegal and destructive logging in Sumatra in its July 2010 report, How Sinar Mas is Pulping the Planet. It runs through each of the claims laid out in the Greenpeace report, arguing some are speculative or improperly cited. But the audit doesn’t actually deny that APP is clearing forests and peatlands for pulp plantations. In fact, the audit effectively confirms that the company is indeed engaged in conversion of ‘deep’ peat areas, but argues that this activity isn’t illegal under Indonesian law.

(08/19/2010) Sinar Mas, an Indonesian conglomerate whose holdings include Asia Pulp and Paper, a paper products brand, and PT Smart, a palm oil producer, was sharply rebuked Wednesday over a recent report where it claimed not to have engaged in destruction of forests and peatlands. At least one of its companies, Golden Agri Resources, may now face an investigation for deliberately misleading shareholders in its corporate filings.

(07/29/2010) Many of the environmental issues facing Indonesia are embodied in the plight of the orangutan, the red ape that inhabits the islands of Borneo and Sumatra. Orangutan populations have plummeted over the past century, a result of hunting, habitat loss, the pet trade, and human-ape conflict. Accordingly, governments, charities, and concerned individuals have ploughed tens of millions of dollars into orangutan conservation, but have little to show in terms of slowing or reversing the decline. The same can be said about forest conservation in Indonesia: while massive amounts of money have been put toward protecting and sustainable using forests, the sum is dwarfed by the returns from converting forests into timber, rice, paper, and palm oil. So orangutans—and forests—continue to lose out to economic development, at least as conventionally pursued. Poor governance means that even when well-intentioned measures are in place, they are often undermined by corruption, apathy, or poorly-designed policies. So is there a future for Indonesia’s red apes and their forest home? Erik Meijaard, an ecologist who has worked in Indonesia since 1993 and is considered a world authority on orangutan populations, is cautiously optimistic, although he sees no ‘silver bullet’ solutions.

How Greenpeace changes big business

(07/22/2010) Tropical deforestation claimed roughly 13 million hectares of forest per year during the first half of this decade, about the same rate of loss as the 1990s. But while the overall numbers have remained relatively constant, they mask a transition of great significance: a shift from poverty-driven to industry-driven deforestation and geographic consolidation of where deforestation occurs. These changes have important implications for efforts to protect the world’s remaining tropical forests in that environmental groups now have identifiable targets that may be more responsive to pressure on environmental concerns than tens of millions of impoverished rural farmers. In other words, activists have more leverage than ever to impact corporate behavior as it relates to deforestation. A prime example of this power is evident in a string of successful Greenpeace campaigns, which have targeted some of the largest drivers of deforestation, including the palm oil industry in Indonesia and Malaysia and the soy and cattle industries in the Brazilian Amazon. The campaigns have shared a common approach: target large, conspicuous consumer-facing companies that sell in western markets.

Nestle caves to activist pressure on palm oil

(05/17/2010) After a two month campaign against Nestle for its use of palm oil linked to rainforest destruction spearheaded by Greenpeace, the food giant has given in to activists’ demands. The Swiss-based company announced today in Malaysia that it will partner with the Forest Trust, an international non-profit organization, to rid its supply chain of any sources involved in the destruction of rainforests. “Nestle’s actions will focus on the systematic identification and exclusion of companies owning or managing high risk plantations or farms linked to deforestation,” a press release from the company reads, adding that “Nestle wants to ensure that its products have no deforestation footprint.”

Certified sustainable palm oil sales reach record level

(04/09/2010) Sales of palm oil certified under the green criteria set by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) reached a record high in March, climbing nearly 8 percent over February 2010 to 136,000 metric tons, reports the RSPO in its monthly bulletin.

Nestle’s palm oil debacle highlights current limitations of certification scheme

(03/26/2010) Last week Nestle, the world’s largest food processor, was caught in a firestorm when it attempted to censor a Greenpeace campaign that targeted its use of palm oil sourced from a supplier accused of environmentally-damaging practices. The incident brought the increasingly raucous debate over palm oil into the spotlight and renewed questions over an industry-backed certification scheme that aims to improve the crop’s environmental performance.

A new world?: Social media protest against Nestle may have longstanding ramifications

(03/20/2010) The online protest over Nestle’s use of palm oil linked to deforestation in Indonesia continues unabated over the weekend. One only needed to check-in on the Nestle’s Facebook fan page to see that anger and frustration over the company’s palm oil sourcing policies, as well as its attempts to censor a Greenpeace video (and comments online), has sparked a social media protest that is noteworthy for its vehemence, its length, and its bringing to light the issue of palm oil and deforestation to a broader public.

Blackwashing by NGOs, greenwashing by corporations, threatens environmental progress

(11/12/2009) Misinformation campaigns by both corporations and environmental groups threaten to undermine efforts to conserve biodiversity and reduce environmental degradation, argues a new paper published in the journal Biotropica. Growing concerns over climate change and unsustainable resource extraction have put companies that exploit the environment in the spotlight. Some firms have responded by taking measures to reduce their environmental impact. Others have alternatively engaged in sophisticated marketing campaigns intended to mislead consumers on their environmental performance, maintaining that environmentally-destructive practices are instead benign. At the same time some activist groups have been guilty of exaggerating claims of environmental misconduct in order to boost support for their campaigns and therefore their fundraising efforts.

Changing drivers of deforestation provide new opportunities for conservation

(12/09/2009) Tropical deforestation claimed roughly 13 million hectares of forest per year during the first half of this decade, about the same rate of loss as the 1990s. But while the overall numbers have remained relatively constant, they mask a transition of great significance: a shift from poverty-driven to industry-driven deforestation and geographic consolidation of where deforestation occurs. These changes have important implications for efforts to protect the world’s remaining tropical forests in that environmental lobby groups now have identifiable targets that may be more responsive to pressure on environmental concerns than tens of millions of impoverished rural farmers. In other words, activists have more leverage than ever to impact corporate behavior as it relates to deforestation.

Palm oil lobby group launches public relations push to counter environmental complaints

(11/02/2009) A report released by World Growth International in late September claimed that environmentalists are waging a “morally indefensible” campaign against palm oil. The report accurately highlighted the high productivity of oil palm — the world’s highest-yielding commercial oilseed — and noted that the crop has created jobs and driven rural development in Malaysia and Indonesia. Critically, World Growth also downplayed chief concerns about the rapid expansion of oil palm cultivation across southeast Asia, notably worries that palm oil production is contributing to deforestation, putting endangered wildlife like the orangutan at risk, and adversely affecting climate. To make its case, the report made some questionable claims, asserting that oil palm plantations sequester more carbon than natural forests and that deforestation is driven by poverty rather than industrial activities.

Britain bans palm oil ad campaign

(09/09/2009) Britain’s Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), a group that regulates advertisements, has again banned “misleading” ads by the palm oil industry, reports the Guardian. ASA ruled that a campaign run by the Malaysian Palm Oil Council (MPOC) makes dubious claims, including that palm oil is the “only product able to sustainably and efficiently meet a larger portion of the world’s increasing demand for oil crop-based consumer goods, foodstuffs and biofuels.” The ad said criticism over “rampant deforestation and unsound environmental practices” were part of “protectionist agendas” not based on scientific fact. ASA held the ad breached several of its advertising standards codes, including “substantiation,” “truthfulness,” and “environmental claims.” In rebuking the MPOC, the ASA said that the merits of new eco-certification scheme promoted by the palm oil industry is “still the subject of debate” and that the ad’s attacks on detractors implied that all criticisms of the palm oil industry “were without a valid or scientific basis.”

Concerns over deforestation may drive new approach to cattle ranching in the Amazon

(09/08/2009) While you’re browsing the mall for running shoes, the Amazon rainforest is probably the farthest thing from your mind. Perhaps it shouldn’t be. The globalization of commodity supply chains has created links between consumer products and distant ecosystems like the Amazon. Shoes sold in downtown Manhattan may have been assembled in Vietnam using leather supplied from a Brazilian processor that subcontracted to a rancher in the Amazon. But while demand for these products is currently driving environmental degradation, this connection may also hold the key to slowing the destruction of Earth’s largest rainforest.

How satellites are used in conservation

(04/13/2009) In October 2008 scientists with the Royal Botanical Garden at Kew discovered a host of previously unknown species in a remote highland forest in Mozambique. The find was no accident: three years earlier, conservationist Julian Bayliss identified the site—Mount Mabu—using Google Earth, a tool that’s rapidly becoming a critical part of conservation efforts around the world. As the discovery in Mozambique suggests, remote sensing is being used for a bewildering array of applications, from monitoring sea ice to detecting deforestation to tracking wildlife. The number of uses grows as the technology matures and becomes more widely available. Google Earth may represent a critical point, bringing the power of remote sensing to the masses and allowing anyone with an Internet connection to attach data to a geographic representation of Earth.

How to save the Amazon rainforest

(01/04/2009) Environmentalists have long voiced concern over the vanishing Amazon rainforest, but they haven’t been particularly effective at slowing forest loss. In fact, despite the hundreds of millions of dollars in donor funds that have flowed into the region since 2000 and the establishment of more than 100 million hectares of protected areas since 2002, average annual deforestation rates have increased since the 1990s, peaking at 73,785 square kilometers (28,488 square miles) of forest loss between 2002 and 2004. With land prices fast appreciating, cattle ranching and industrial soy farms expanding, and billions of dollars’ worth of new infrastructure projects in the works, development pressure on the Amazon is expected to accelerate. Given these trends, it is apparent that conservation efforts alone will not determine the fate of the Amazon or other rainforests. Some argue that market measures, which value forests for the ecosystem services they provide as well as reward developers for environmental performance, will be the key to saving the Amazon from large-scale destruction. In the end it may be the very markets currently driving deforestation that save forests.

Shift from poverty-driven to industry-driven deforestation may help conservation

(08/06/2008) A shift from poverty-driven deforestation to industry-driven deforestation in the tropics may offer new opportunities for forest conservation, argues a new paper published in the journal Trends in Evolution & Ecology.