- Agropalma, the only Brazilian company with the sustainability certificate issued by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), is accused of a wide range of land-grabbing allegations in Pará state.

- The claims allege that more than half of the 107,000 hectares (264,000 acres) registered by Agropalma was derived from fraudulent land titles and even the creation of a fake land registration bureau, which is at the center of a legal battle led by state prosecutors and public defenders.

- Quilombola communities say that part of the area occupied by Agropalma overlaps with their ancestral land, including two cemeteries visited by Mongabay. In one of them, residents claim that just one-quarter of the cemetery remains and that the company planted palm trees on top of the graves, which the company denies.

- There are also other financial interests in the land at stake, researchers say, pointing to the company’s moves into bauxite mining and the sale of carbon credits in the areas subject to litigation, further intensifying the disputes.

ALTO ACARÁ, Brazil — With trembling hands, Raimundo Serrão lights candles for his grandmother at the Livramento Cemetery’s cross on the Day of the Dead because he couldn’t find her grave. Serrão and others in the area say one of the country’s leading palm oil exporters has buried it under palm crops.

“They have planted palm trees on top of her grave,” Serrão tells Mongabay in tears, blaming Agropalma, whose palm oil plantations engulf the cemetery on the banks of the Acará River in northern Pará state in the Brazilian Amazon. “She is underneath this palm oil [plantation] there,” he says, pointing to nearby palm trees, an area he says was part of the cemetery when she died at the age of 110 in 1978, a claim the company denies.

The accusations are part of a wide range of land-grabbing allegations against Agropalma, the only Brazilian company with the sustainability certificate issued by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a members organization including palm oil growers, traders, manufacturers, retailers, banks, investors and others.

Mongabay visited Alto Acará in November 2021 to investigate accusations that more than half of the 107,000 hectares (264,000 acres) registered by Agropalma was derived from fraudulent land titles and even the creation of a fake land registration bureau, which is at the center of a legal battle led by state prosecutors and public defenders.

Serrão is a Quilombola, a descendant of Afro-Brazilian runaway slaves. He is one of a dozen Quilombola leaders who guided Mongabay along the Acará River and dusty roads, surrounded by palm oil crops and land considered Agropalma’s “legal reserve,” a classification that obliges private property owners to preserve a portion of their land for native vegetation.

Quilombola communities say that part of the area occupied by Agropalma overlaps with their ancestral land, including two cemeteries visited by Mongabay. The Livramento Cemetery is confined in oil palm crops and has a grave dated 1928; we also saw the remains of a chapel, a school, and a kitchen in the area registered as Agropalma’s legal reserve, where the Our Lady of Battle Cemetery is located.

In its legal battle, the Public Defender’s Office says the existence of four Quilombola and Indigenous cemeteries in areas occupied by Agropalma between the municipalities of Acará and Tailândia is a critical piece of evidence of the communities’ right to the land. “One of the main issues to us are the cemeteries. Because they’re an indication that there was a community [in the region],” agrarian public defender Andreia Barreto says. “We have a list of their relatives who were buried, we have a list of the families who are in those cemeteries.”

Over the past year, we sifted through thousands of pages of documents to investigate the land-grabbing accusations against Agropalma, which is responsible for a quarter of the country’s palm oil exports, according to Trase, a research group run by the Stockholm Environment Institute and the NGO Global Canopy.

“These areas had problems regarding the detachment of public property to the private sector. They are still state public lands,” state prosecutor Ione Nakamura, who has led the case since 2021, tells Mongabay.

State prosecutor Eliane Moreira, who filed two lawsuits in 2018 and 2020 in an attempt to cancel Agropalma’s titles, says there is “no doubt” about the fraud that at first glance seems “such an unthinkable story.”

“It’s so elaborated that they created a fictitious notary’s office. … It’s many areas, it’s a mosaic. … What unites them all is an intervention of a “cartório,” which is a notary’s office that never existed that produced documents that were apparently very reliable,” Moreira tells Mongabay. “And there is also the intervention of a notary who was no longer in business who issued documents.”

In a six-year legal battle to prove fraud and charge Agropalma to pay compensation for “collective moral damage” due to the illegal occupation of public land, the court ordered the company’s property titles to be revoked in 2018 and 2020; its decisions were upheld by other courts in the following years. Despite admitting the deeds were counterfeited, the company claims it was not involved in the scheme. It is now seeking to repurchase the land from Pará state.

Beyond Agropalma’s core business of palm oil, there are also other financial interests in the land at stake, which researchers say further intensifies the disputes. They point to the company’s moves into bauxite mining and the sale of carbon credits in the areas subject to litigation, in disregard of court decisions canceling the land titles.

“All these are pressure fronts that are suffocating, choking these people who are fighting to return to their territory,” says researcher Elielson Pereira da Silva, who has conducted research in the area since 2019 for the Federal University of Pará (UFPA).

Obstacles to visit cemeteries

Since Agropalma started taking possession of areas in the region in the 1980s, Quilombolas say they haven’t been able to access the Our Lady of Battle Cemetery, located inside the company’s legal reserve. Tired of waiting for a court ruling, last year they decided to go to the cemetery to clean the area and the graves and light candles to honor their ancestors on the Day of the Dead.

“Four of my sons are buried here,” smallholder Benonias Batista tells Mongabay through tears while lighting candles for his children. “After [the company] took it over, they haven’t allowed us to come here anymore.”

Agropalma says it did not prevent Quilombolas from going to the cemetery, as they are freely allowed to visit the site through the river path, not through the company’s property. The Quilombolas say they always used this path before the company’s arrival.

“There was no road in that area before the plantation,” Tulio Dias Brito, Agropalma’s director of sustainability, tells Mongabay in a video call. According to Brito, to use the company’s road, visitors must be identified at the company gate, where documents such as driver’s and vehicles’ licenses are checked. “There is a series of bureaucracies that the law obliges us to do, which many times people perceive as an impediment to passing through. And in fact, it is not.”

Experts criticize the restrictions, arguing that it breaks Brazil’s Constitution. “The right of those who used to live here to access the cemetery is in the Constitution. The cemetery is a sacred place,” sociologist and historian Maria da Paz Saavedra, a UFPA researcher and PhD candidate, says during a visit to the area.

“There is an enclosure there. Not just physical, in the sense of the palm crops, but [also] an enclosure in many ways,” Silva tells Mongabay at the center of the Our Lady of Battle Cemetery. “These people are prevented from being who they are,” adds the researcher, who has a PhD in sciences with an emphasis in socio-environmental development and was Pará’s regional superintendent of the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA) from 2008 to 2013.

As well as access to the cemeteries, the communities in the Alto Acará region are also fighting to have Quilombola identity and land rights officially recognized. Since 2016, they have been waiting for a response from the Pará land institute, Iterpa, following a request to demarcate at least 18,000 hectares (44,479 acres) — most of it occupied by Agropalma — for the collective use of the Acará Valley’s Association of Quilombola Remnants from the Balsa, Turiaçu, Gonçalves and Vila Palmares Communities (ARQVA), a community network.

Batista showed Mongabay around the area he says he founded and was where he lived until it was declared Agropalma’s legal reserve, just a few steps from the Our Lady of Battle Cemetery. “Here was the chapel, the church. … This was the dance hall. On Saturdays, we used to organize gatherings, to entertain people. This floor was our main hall. Right here,” he says, pointing to the remains of buildings in the area.

Brito challenges the argument that the existence of cemeteries in the company’s areas proves their ancestral right to the land. He said the company believed the cemetery was created by a family descended from Portuguese colonists.

He also challenges the Quilombolas’ rights over the area, citing a 2018 report from Iterpa, which denied the existence of traces of the community in the area in dispute. “There is a doubt, at least on Iterpa’s part, whether the community is Quilombola or not,” he says. “The representatives of the entity were together with the movement’s leaders visiting and mapping the place, but found no evidence of current or ancestral Quilombola communities in the claimed area,” Brito wrote in an email in December 2021.

As reported by Mongabay last year, the presence of several centenary Quilombola settlements, or quilombos, was similarly ignored during the licensing process for the palm oil industry as a 2010 agroecological zoning program for palm oil cultivation in deforested areas called ZAE-Dendê overlapped with traditional Quilombola communities. The Palmares Cultural Foundation, a public institution set up to defend Afro-Brazilian culture, didn’t respond to Mongabay’s request for comment about both the Quilombolas’ self-identification process and their land claims.

Barreto and researchers such as Saavedra and Silva have challenged Iterpa’s findings, as they weren’t made by anthropologists or independent experts. Their joint research, along with anthropologist Rosa Acevedo Marin for UFPA, points to evidence of the existence of slaves and Quilombola communities in the Alto Acará region. The study states that in the last four decades, residents were expelled from the banks of the Acará River, under pressure from land-grabbers who cheated the communities into selling the land before reselling it to Agropalma. According to the research and residents who spoke to Mongabay, violence was also used to persuade residents to sell.

The Public Defender’s Office and researchers challenged Iterpa with the evidence from the study and requested a review.

A map published in September by the nonprofit Global Witness shows the overlap of the claims by Quilombola and traditional communities’ over areas under Agropalma’s possession.

Brito denies that the company planted palm trees on cemeteries. “This is not true,” he says, adding that the company consulted with several elderly locals who had not raised concerns. “We were able to conduct eight interviews. Seven of them stated categorically that there is no palm oil in the cemetery. All of them have relatives buried there,” he adds, pointing out that the only critical person didn’t back up the complaints.

“We don’t understand that the cemetery legitimizes anyone’s right to the areas that are around the cemetery. But we do understand that the cemetery is a sacred area,” Brito says. “It is an area that should never be touched. And that the community has every right to go there.”

Global Witness’ map is part of a report covering conflicts between traditional communities and palm oil companies, including Agropalma. The report also tracks Agropalma’s 20 importers. “The fact that all multinational companies who responded to Global Witness claim to be aware of the conflicts in their Brazilian palm oil supply chains and continue to purchase palm oil from [Brasil BioFuels] BBF and/or Agropalma indicate that they have completely failed to prevent or mitigate human rights abuses occurring in this region of Pará,” Global Witness states in the report.

Subsidiary of the Brazil-based Alfa conglomerate — a major player in the finance, insurance, agribusiness, building materials, communications, leather and hotel sectors — Agropalma recorded revenues of 1.4 billion reais ($270 million) in 2020. Its production sets around 160,000-170,000 tons of oil annually — the largest “sustainable” palm oil production in the Americas — which it intends to increase by 50% until 2025, according to the company’s website.

Root of problem: unreliable land titles

At the heart of the Amazon, Pará has some of the country’s worst deforestation rates, as well as rampant illegal logging, land-grabbing and murders of land activists. Experts say the root of these problems is the state’s troubled land ownership system.

Land-grabbing is one of the main drivers of deforestation. With an antiquated and unclear land registration system dating back to the colonial period, Brazil lacks a centralized system to check who owns the land, a key instrument to avoid fraud.

Instead, land titles are issued by some thousands of real estate registry offices, which are held by public service delegations, known as cartórios, which don’t communicate with each other. As a result, multiple allocations for a single area are not uncommon, particularly in the Amazon, along with corruption claims tied to the issuance of title deeds, including the involvement of public servants allowing public land to be unduly occupied by private owners.

In Agropalma’s case, the prosecutors’ investigation was first triggered by claims from a family in Pará’s capital Belém, who argued that Agropalma seized areas belonging to the family through a land-grabber who multiplied the area they sold from 2,678 hectares (6,617 acres) to 35,000 hectares (86,487 acres). While the prosecutors don’t act for the family, whose case is ongoing in the courts, the family’s claims led to investigations into Agropalma’s alleged land-grabbing in Pará state.

“The news comes to us through this family. … We investigated and verified that there were foundations there,” Moreira told Mongabay at her office in Belém in August 2019, when this reporter first started investigating these land grab claims. Following further investigation, Pará State’s Public Ministry filed class action lawsuits in 2018 and 2020, seeking to revoke Agropalma’s land titles. As each area has a different problem, Moreira explains, she ended up dividing it into seven blocks according to the irregularities. “These lands have to go back to the public patrimony.”

Agropalma recently requested the cancellation of the titles following the lawsuit. “The company claims that now in the course of the process, they themselves asked [for the cancellation]. … But they only took action after we filed the lawsuit.”

Moreira adds that the company should also be charged and ordered to pay damages, as “who does land-grabbing causes damage to record keeping. Public registration is a very serious thing. If someone introduces fraudulent information … he causes damage to the public record system.”

Brito denies the accusations that the company has unlawfully occupied public land. “Actually, we didn’t appropriate [the land]. We bought land. We bought land over a long period of time. We started buying land there in ‘81 and have been buying land until the 2010s,” he says. “We understand that yes, our titles have been canceled. They are temporarily canceled, and we will appeal. But the possession is ours.

“We bought [land] from the supposed owner at the time, in good faith. We paid the market price. We registered it in the notary’s office. Everything we did was transparent.”

He says that Forest Code and the Land Statute state that “who is in possession has the domain of that unit,” and “our possession is legitimate. It is peaceful. It is registered.”

Prosecutors are also seeking the withdrawal of Agropalma’s RSPO certificate. Through this certificate, Agropalma exported 21,941 tons in 2017, the latest available data disclosed by Trase. The land titles “should not be generating the legal effects that they are generating. That’s why we also filed against the certifier,” Moreira says, referring to IBD Certifications Ltd. (IBD), the group responsible for the certification process in Brazil. “We understand that they have the obligation, once they are aware of the situation, to also adopt the measures.”

“By bearing the aforementioned RSPO seal, the company validates itself in the market before its competitors and consumers as a company that complies with the legislation in force, which, as already demonstrated, does not match reality before the practice of conduct that is harmful to the registration system,” Moreira wrote in the lawsuit, urging the withdrawal of the certification.

IBD did not respond to Mongabay’s recent request for comment. In a statement from 2020, IBD said it “responds only to customers, the RSPO and legal authorities in the country.” In an emailed statement, the RSPO secretariat said IBD’s scope of RSPO Principles & Criteria (P&C) worldwide was suspended on June 8, without providing details why.

Regarding the court proceedings of the case, RSPO says it has not received any information regarding its progress. “Once a case goes to court, RSPO are solely observers of the legal process. As the matter is now being heard by the Courts, RSPO respects the local legal process and leaves judgement to the courts to determine the Complainants’ claim,” RSPO says.

RSPO adds that palm oil producers are certified through “strict verification of the production process to the stringent 2018 RSPO Principles & Criteria (P&C) for sustainable palm oil production by accredited Certification Bodies (CBs)” and that it “takes every effort to ensure that its certified members uphold the P&C.” Moreira also charges Iterpa in the lawsuit for having improperly used the false documents to issue definitive titles to Agropalma and for continuing the company’s land regularization process. Iterpa did not respond to Mongabay’s request for comment regarding the lawsuits.

The prosecutor’s requests regarding the suspension of Agropalma’s land regularization process and the suspension of its RSPO certificate, however, have been denied by courts so far.

New frontiers

Researchers say they are concerned about other businesses that Agropalma aims to expand, including bauxite mining and carbon credit trading, despite having had most of the land titles of the areas canceled by court decisions.

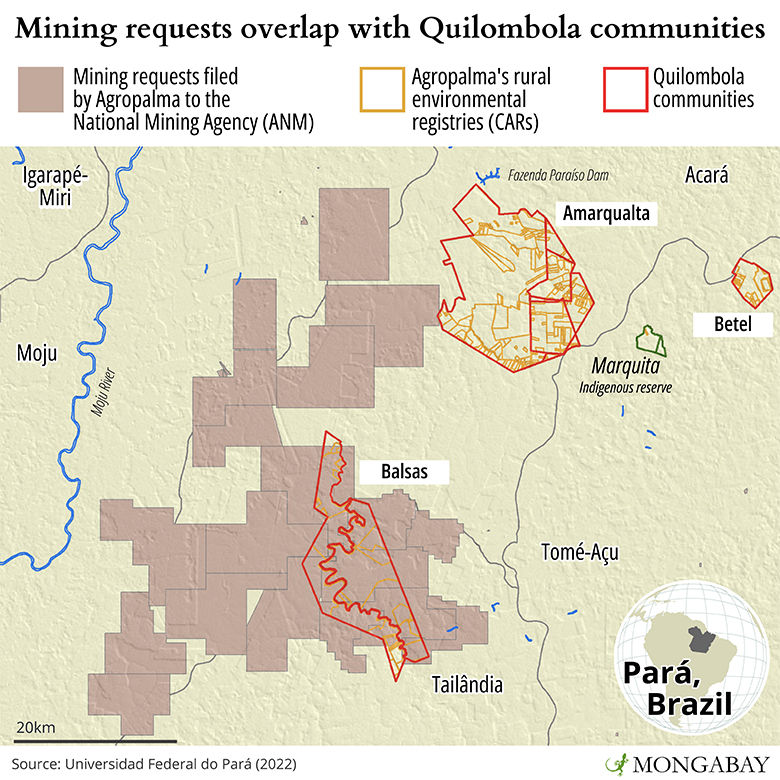

According to recent research by Silva of UFPA, Agropalma has made 17 requests for research authorization for bauxite mining covering 121,000 hectares (299,000 acres) in the Alto Acará region. Part of these requests cover areas claimed by Quilombola communities as their ancestral lands, including Our Lady of Battle Cemetery.

“The result is shocking,” Silva told Mongabay in a phone interview in October, referring to cross-referencing locations of Agropalma’s rural environmental registries (CARs) and the mining requests.

The research shows that Agropalma’s exploration permits expired between 2018 and 2019, after which the company requested an extension for 88.2% of the permits. The mining regulatory agency ANM denied the company’s initial requests, Silva says, and the company is appealing the decision.

Agropalma’s Brito, however, says the company had no intention of extracting bauxite from the areas in question. Instead, the company applied for the research licenses to protect their claims to the land, he adds. “With us having the right to do research, we’re given security that the areas will continue to be protected. … While you have the authorization for mineral research, no one else can ask for it,” he says.

Silva has also raised concerns about an ongoing proposal to create an “ecological corridor” bringing together areas of “private reserves” of oil palm companies in Alto Acará, including Agropalma. According to him, the initiative will allow the sale of carbon credits and overlap with lands traditionally occupied by Quilombolas.

According to Brito, while the project would increase the quality of preservation and biodiversity in the company’s legal reserve, the carbon credit studies are ongoing and “will take some time and will also have to analyze the Quilombola issue.”

In an emailed statement in October, Agropalma said it announced last year a partnership with a consulting firm specializing in forest conservation and the “commercialization of environmental services” for the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) project, an incentive developed under the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). “With the project, Agropalma will not only be an emissions neutral company, but will also contribute so that other companies can do their part to combat climate change.”

The project “will enable the selling of carbon credits starting in 2023, considering that the company has negative emissions,” according to a news release on the company’s website.

Contamination

Agropalma is also accused of contaminating the rivers and streams with a palm oil residue known as tibórnia that is used as fertilizer on the crops. “This morning we woke up in the Palmares village smelling the tibórnia. … They throw it on the fields, close to the palm trees. And it drains into the streams. … But this is really harmful. Not only due to its strong smell, but also because it causes nausea and headaches,” Silva says.

The researcher recalls the first time he smelled the tibórnia’s stink, when he witnessed the moment of its application on palm crops in June 2021. He says that staying for three or four minutes to take photos and videos “was enough for me to have a headache for two days, and there was no medicine to alleviate these pains. … It was a very difficult feeling, very horrible indeed. Pains and retching, that agony. And I stayed there for three minutes. Imagine the people there, permanently exposed because you have a village [Palmares village] with more than 10,000 residents, which is surrounded by oil palms on all sides.”

In Tomé-Açu — a production area of another palm oil company in Pará close to the Turé-Mariquita Indigenous Reserve — Mongabay found water contamination from pesticides used in palm oil crops that caused the same nausea and headaches described by Quilombolas and the researcher. This reporter experienced a rapid onset of coughing, shortness of breath, nausea and headaches after inhaling fumes from these oil palm trees doused with pesticides during an investigation in the region in 2019.

Brito says the substance the company applies in a limited area is a type of liquid fertilizer approved by Pará’s environmental department, SEMAS, which is not harmful to health, as it derives from an organic process.

“There is no chemical product there. And that, basically, is fruit, the aqueous part of the fruit, which is not oil and is not solid either, [which] went into the effluent,” he says, adding that extra water is also added before it goes through an anaerobic treatment in lagoons. “And we did a ferti-irrigation system, as established by the secretary of environment. It is in our environmental license, which has to be applied this way.

“I’ve been exposed for hours, and I’ve never had anything. In theory, you are not supposed to have anything at all,” he says. “And our application area on the farm, the piece that is closest to the village of Palmares is 2,750 meters from the village of Palmares.”

SEMAS did not reply to Mongabay’s request for comment.

Fight for recognition

As well as the land disputes with Agropalma, there are also conflicts over areas used by other palm oil companies. In Balsa village, on the banks of the Acará River, communities who were already displaced from other areas, including Quilombolas, are now stuck in limbo after being removed to make way for the pavement of a road used to transport oil palm fruits and other commodities.

One of the most touching cases is 96-year-old Maria Julieta Gonçalves da Conceição, who has lived in the area since she was a kid, when she planted a nut tree — the only one remaining in the village.

“Our house was right here, where there’s this nut tree. This is my tree, my mother and my father’s too. This is where our farm used to be,” she tells Mongabay. “Here [was] the Urucuré farm and they wanted to take it [the tree] down. They knocked down all the other trees. They had the chainsaw next to [the tree]. But I didn’t let them do it.”

She has been living with 10 people, including her daughter and grandchildren, for about 35 years in a shack next to the unpaved PA-256 road. “There’s a lot of noise here. We can’t even sleep during the night,” she says.

Julieta says she has become sick with heart and blood pressure issues and shortness of breath, as she suffers from the risk of being displaced. “It’s heart [issues]. It’s shortness of breath. I suffer. And there are nights that I don’t sleep. I wake up almost crazy, I’m falling, holding on to the walls. … We don’t have anywhere to go. There isn’t a place for people here,” she tells Mongabay in tears. “I’m very happy here, this is my place. … I was born and raised in this place, I never abandoned Acará. … I’m here until the end of my life.”

Balsa village is included in ARQVA’s request as an area that would be allocated for the Quilombolas’ right of return. Barreto, the public defender, says she is concerned that without a favorable court decision, the advancement of the road project — led by the Pará state government and financed by BRICS’ New Development bank — will make future progress on the case impossible.

“The licensing process of the road, the families’ registration [as displaced] is proceeding faster than the [land demarcation] process of Iterpa itself, which was opened in 2016. So, the longer the process takes, the longer the state does not give an answer to the community, the more this community becomes fragile.” The Pará government didn’t respond to Mongabay’s request for comment.

Barreto, Silva and Saavedra say residents should have the right to return to where they lived in the past. They argue that after Agropalma came to the area in the 1980s, many residents were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands.

“My dad had a plot of land right down here. … [Agropalma’s representative] convinced him to leave the area. … He said: ‘You have to sell it, there’s no use in being here because the company has the documents. So you will have to leave anyway. This is not yours,'” fishermen Adilson José Pimenta tells Mongabay on the banks of the Acará River. According to him, his dad had to accept little compensation and moved elsewhere. “That’s what happened to everyone [in this area].”

Serrão says he and his family remained alive following gunmen’s threats only because his dad forcibly accepted a small amount of money for the land on the Acará River’s bank where his formerly enslaved ancestors escaped to in the early 1900s. “The worst was going to happen, he was going to kill him there and he was going to kill the rest of the family. Because he wasn’t going to let anyone live.” The area is now under Agropalma’s possession, he says.

“This farmer … bought [the land] from the people who used to live next to me. He fooled us by buying our land very cheap,” Francisco Neves Costa, an Indigenous laborer who lives in Balsa village, tells Mongabay. “Back then we were all almost illiterate, we didn’t really understand things. [The buyer] came with very little money and duped people. Everybody felt threatened and scared.”

Costa says he and his family were displaced a few times since he was a child. “I don’t even know exactly where I was born. I know I was born on the banks of the Acará River, downstream. Now it all belongs to Agropalma. The people who lived there … they all left, threatened as well.”

Agropalma denies using violence to acquire land. Following the residents’ claims, Agropalma’s Brito says, the company interviewed a dozen people in the area, including those critical of the company, and none of them reported violence or gunshots.

“This is a very ancient area of occupation. … What I can tell you is the following: Everyone, including the person who was very much against Agropalma, I asked: Have you ever seen someone on behalf of Agropalma, be it Agropalma security, or any intermediary, someone speaking on behalf of Agropalma, threatening or expelling people from here? ‘Oh no. I never saw.’ Even a guy who was against it,” he says. “Speaking for the company itself, we were never threatening anyone.”

Researchers say that Neves’ case is a clear example of “ethnocide” faced by the displaced traditional communities in Alto Acará in the aftermath of palm oil monoculture. When asked if he was a Tembé, an Indigenous people living in Amazonas and Pará states, he says: “Even today I have doubts, you know? Everybody died and I was young. I know that my father was Indigenous. My grandmother was Indigenous.”

Like Neves, several Tembé Indigenous people were displaced from their ancestral land, researchers say.

In Palmares village, a community surrounded by Agropalma’s crops to where the majority of displaced residents moved, Nitônia dos Santos, of the Tembé people, says she remembers when she and her family suddenly had to leave their house close to the Acará River after her father told them “it was sold” by a non-Indigenous land-owning family who transferred the deeds to Agropalma.

Cemeteries uniting Indigenous and Quilombolas

The situation in Alto Acará worsened this year, Quilombolas and experts say. Tired of waiting for a legal response, in February, a group of some 60 Quilombolas occupied the claimed area of the Our Lady of Battle village, triggering another round of legal wrangling over the area.

Agropalma reacted immediately “taking all measures to protect its employees and assets” to get the “invaders” out of the area, Agropalma’s Brito said in an email in February. Security cabins and surveillance towers were also installed, residents say, further restricting the Quilombolas’ access to the area and the river, which they rely on for fishing.

“We are creating barriers with truck buckets and digging ditches, making access difficult to prevent more people from reaching the site. This right to self-protection is guaranteed by law (right to immediate relief) and in 40 years of existence, this is the first time that Agropalma has had to adopt this type of measure,” Brito wrote in an email at the time, adding that the ARQVA leaders were not willing to dialogue with the company and said that “they will only leave the area with a court decision.”

Following the conflict, now only residents whose names are on an approved list can enter the area, Barreto says. Surveillance towers close to the cemeteries and along the river also remain in place.

“The river is a problem. And it’s absurd to privatize the river, saying that it’s patrolling the river,” Barreto says. “They’ve always lived there. … They are not professional fishermen. They don’t need to be authorized.”

While Barreto disagrees with all these measures, she says it’s not worth continuing the standoff.

“They are focusing on a single process that the company itself has judicialized, which is the possessory action, but they are not facing the central problem, which is the destination of the public land and the non-conclusion of the Quilombola process, which is also at Iterpa. This is the great debate.”

Iterpa is yet to make public its new report into the Quilombolas’ claims, but it won’t recognize the Quilombolas’ rights over the Our Lady of Battle and Balsa villages and other claimed areas due to the lack of evidence, according to a copy of the report seen by Mongabay. “But that is not our thesis. Our thesis is that the cemeteries are already evidence. That is why we are asking for expertise in the area because of the cemetery itself,” she says.

Following the occupation of the Our Lady of Battle village, a group of some 60 Indigenous Tembé, including Neves, are also fighting for recognition and sent a self-declaration document in September to the Indigenous affairs agency, Funai. According to studies by Silva, Paz and Marin, they’ve been displaced and scattered around the communities in the region and have a relationship of proximity, of kinship, with the Quilombolas.

“Sacred spaces, the cemeteries have been constituted as an element of mobilization of the Indigenous and Quilombolas,” Silva says. “These Indigenous people signed an act, a document recognizing themselves as Indigenous, describing the whole process of violent expulsion that they were subjected to, and sent a letter to Funai.”

In the letter seen by Mongabay, Sipriano dos Santos Campos, a Tembé Indigenous chief — or cacique — from Turi-Açu Village told Funai: “We, the displaced Indigenous, have been violently expelled from our territory, situated in Itapeua, in Alto Acará, since the 1970s, when large oil palm plantations were set up. Today, we live in complete economic dependence on non-Indigenous people, wandering around in search of work.”

According to Campos, they still preserve a few traditional customs despite being “confined and isolated in the midst of large latifundia, especially oil palm plantations” and he urged “to recover the territory from which we were expropriated, an essential factor for the survival of the group.”

He requested Funai to carry out the necessary studies for the recognition of the Tembé traditionally occupied ancestral lands that “were taken by force by gunmen and land-grabbers at the service of farmers and agribusiness mega-companies.” “To confirm the Indigenous presence prior to the arrival of the ranchers and the oil palm company, in addition to the presence of cemeteries, we have the remains of old domestic utensils found recently in the claimed territory,” he wrote.

“The self-identification process is the result of a conscious mobilization and aims at the restitution of territorial rights historically undermined and denied to our people and, at the same time, to put an end to decades of abandonment, violations, stigmatization, and other ethnocidal practices that threaten our physical, social, and cultural existence.”

Funai did not respond to Mongabay’s request for comment.

Iterpa is accused of favoring Agropalma while speeding up the company’s land registration processes to the detriment of the Quilombola communities, who should take priority.

Agropalma denies the accusation, claiming that its land regularization process stalled due to the Quilombola case.

In an emailed statement, Iterpa didn’t address the accusations and said that “Pará assures in law, in structure and in actions the due legal process necessary to recognize the territorial rights of the remaining quilombola communities.”

Agropalma is also up for sale. Authorities and researchers say they fear the situation could worsen even more, mirroring what happened in the Tomé-Açu region, where violence escalated, following Biopalma da Amazônia’s sale to Brasil BioFuels S.A. (BBF) in 2020, triggering a so-called “palm oil war” as reported by Mongabay. In this case, community leaders and authorities say that previous agreements between Biopalma and the communities have reportedly not been honored under the new ownership. There are also land disputes over areas claimed by both sides, aggravated by Funai’s inaction to demarcate ancestral lands.

In a meeting with Iterpa in October, Barreto says, she signaled that it was necessary to solve the problem that is now incontrovertible, which is the Gonçalves village — the only community Iterpa acknowledged in the report — “because the company had already announced the sale and it’s unknown what the policy of the successor company would be,” which is what already happened to BBF itself. “When the BBF came, a more aggressive policy against communities came.”

“Six years is not six days. This process, in my view, should be over by now,” said José Joaquim dos Santos Pimenta, a Quilombola who leads the ARQVA association, in a meeting with Iterpa in October. In this meeting, an Iterpa representative highlighted “this issue is very complex,” according to a recording assessed by Mongabay.

Barreto, the public defender, urged Iterpa to find a solution to end the conflicts. “While the state of Pará does not give a resolution to the land destination situation, the conflict will continue.”

In fact, a new occupation in the claimed Our Lady of Battle village was triggered in the last days, but now has Quilombolas and Indigenous as protagonists, Silva, the researcher tells Mongabay. “Indigenous Territory: These lands belong to the Indigenous and Quilombola [peoples],” says a poster posted on one of the gates placed by Agropalma to hamper the community’s access to the area through their plantations, following the occupation in February. Silva tells Mongabay that this time, however, Quilombolas and Indigenous people reached the area through another path from the other side of the Acará River, not through the company’s plantations.

Agropalma filed a court complaint arguing that the Quilombolas disobeyed an agreement signed with them after the February occupation; a court hearing is scheduled for Dec.15.

Nakamura, the prosecutor, says that Pará’s legislation is clear when it comes to the prioritization of public land use: the local population. “The [State] Public Ministry stance on this is in favor of acknowledging the rights of the traditional peoples and communities, who are vulnerable and have historically occupied this region for a long time.” According to Nakamura, although Agropalma had invested in the area, “this activity cannot go over the people who already lived here, who have a historical, cultural, ancestral, religious relationship with the land and with their ancestors.”

Despite this years-long legal fight, Pimenta says he tries to remain hopeful of a positive outcome for the Quilombola. “I hope in God and trust in the work of Iterpa that soon we will be receiving the titling of our territory,” he says, adding that he is also hopeful for further land recognition for Quilombolas under the upcoming government of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

Batista, the Quilombola smallholder, says his dream is to see the Our Battle of Battle community active again “to have a nice community here, so we can work, we can produce things that we can [sell] somewhere. Our manioc, our beans, our pumpkin,” he tells Mongabay with great emotion, seated in the debris of a stove he says he built himself in the Our Lady of Battle community. “If we retake the possession of [this land], we will be very happy.”

Serrão, the Quilombola smallholder, says he dreams of returning to his land, from where he was expelled with his family decades ago at gunpoint.

“My dream is to live next to this river. To be free again,” he says close to the area where he was expelled by gunmen. “This river here is our road. We were raised here. This river here is life for us.”

Banner image: Raimundo Serrão lights candles for their departed family members. Image courtesy of Elielson Pereira da Silva.

Karla Mendes is a staff contributing editor for Mongabay in Brazil. Find her on Twitter: @karlamendes

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Related reading:

Déjà vu as palm oil industry brings deforestation, pollution to Amazon