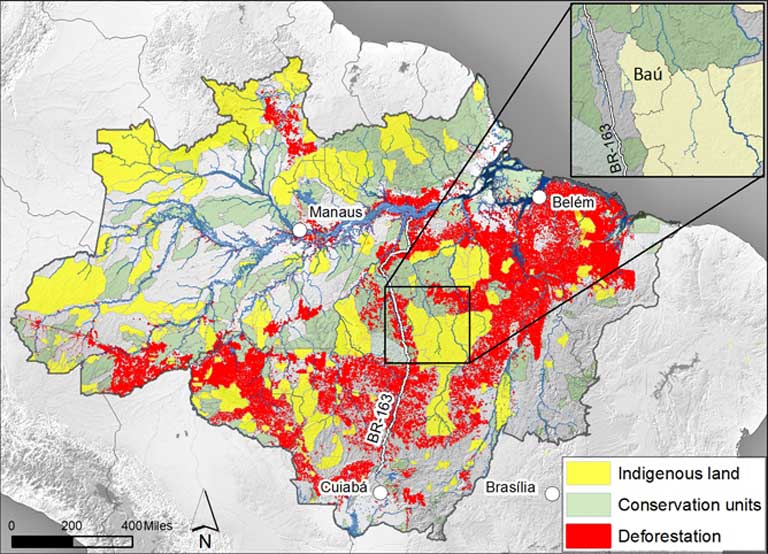

- According to 2014 data for Legal Amazonia, 59 percent of that year’s illegal deforestation occurred on privately held lands, 27 percent in conservation units, 13 percent in agrarian reform settlements, and a mere 1 percent on indigenous lands — demonstrating that indigenous land stewards are the best at limiting deforestation.

- Indigenous groups control large reserves in the Amazon and have the constitutional right to more, but land thieves and agribusiness are working to prevent recognition of new indigenous territories — forested territories that, if protected, could sequester a great deal of climate change-causing carbon.

- While President Lula failed to live up to indigenous expectations, the Dilma and Temer governments, heavily influenced by the agricultural lobby, showed much greater hostility to indigenous needs and demands. Indigenous groups plan a mass protest on April 24-28 to make their grievances known to the Temer government.

- “The Brazilian economy has become increasingly dependent on agribusiness [with] political repercussions.… People [aren’t] against the Indians because they are Indians or because they have too much land. The problem is that the Indians have lands these political actors want.” — Márcio Meira, former head of FUNAI, Brazil’s Indian affairs agency.

(Leia essa matéria em português no The Intercept Brasil. You can also read Mongabay’s series on the Tapajós Basin in Portuguese at The Intercept Brasil)

The Tapajós River Basin lies at the heart of the Amazon, and at the heart of an exploding controversy: whether to build 40+ large dams, a railway, and highways, turning the Basin into a vast industrialized commodities export corridor; or to curb this development impulse and conserve one of the most biologically and culturally rich regions on the planet.

Those struggling to shape the Basin’s fate hold conflicting opinions, but because the Tapajós is an isolated region, few of these views get aired in the media. Journalist Sue Branford and social scientist Mauricio Torres travelled there recently for Mongabay, and over coming weeks hope to shed some light on the heated debate that will shape the future of the Amazon. This is the twelfth of their reports.

“As president of the Kabu Institute, I keep an eye on everyone coming into our forest — gold miners, loggers, farmers (who do most of the deforestation), and so on. We protect our entire area so it will remain as it always was,” indigenous leader Anhë Kayapó told us.

We’d just arrived and introduced ourselves at his office in the town of Novo Progresso in Pará state. Without more ado, he spoke briefly to us about the long indigenous occupation of the land and the Indians’ mistrust of “whites.” Then added brusquely: “That’s all I have to tell you,” ending the interview. He shook our hands firmly and left us alone in the room.

Anhë Kayapó is the leader of the Kayapó Mekrãgnoti, who live in the Indigenous Territory of Baú, which lies to the east of the BR-163 highway. Unlike the Munduruku Indians we’d visited earlier in our trip — highly democratic and famous for long meetings aimed at reaching consensus — the Kayapó are more hierarchical and dislike drawn-out discussions. They prefer action to debate, so the brevity of our meeting didn’t surprise us.

Anhë Kayapó’s distrust of “whites” too is understandable in light of the near perpetual state of conflict that marks the history of indigenous land claims and white settlement in the Amazon — a contentious relationship that seems about to boil over as Brazil’s agribusiness-backed Temer administration pushes ahead with anti-indigenous policies.

Guardians of the forest

The Baú territory inhabited and protected by the Kayapó Mekrãgnoti and other indigenous groups covers 1.5 million hectares (5,800 square miles). When combined with surrounding indigenous territories and conservation units, the land conserved here totals a staggering 28 million hectares (108,000 square miles) — one of the largest protected wild corridors in the world, and a vast swathe vital to conserving Amazon tropical rainforest.

The Kayapó aren’t the only Indians in Brazil to resolutely defend their forest territory against intruders. In fact, the Amazon’s indigenous people do a better job curbing deforestation than any other group of land managers. According to data for 2014 from the Forest Transparency Bulletin of Legal Amazonia, 59 percent of that year’s illegal deforestation took place on privately held lands, 27 percent occurred within conservation units, and 13 percent within agrarian reform settlements. But just 1 percent of deforestation occurred on indigenous lands.

As a result, Brazil’s nearly 900,000 Indians, belonging to 305 ethnic groups and speaking 274 languages, not only make a major contribution to the country’s social and cultural diversity, but they have proven to be unparalleled stewards of ecological diversity as well. And that has made these forest guardians, along with their indigenous reserves, a primary target of those wanting to unleash unregulated development in the region.

But the Indians are fighting back — with Brazil’s 1988 Constitution, agreed to after the end of the military dictatorship, giving them a strong legal basis for their struggle. Until then, indigenous land had only been ceded to Indians provisionally, until they were “assimilated” into so-called “national society.” Among other advances, the new Constitution brought Indians the right to be Indians forever. It was a turning point for indigenous people in a century that had been characterised by massacres. During the 25 years of the military dictatorship alone, it is estimated that at least 8,300 Indians were assassinated.

One key advance under the new Constitution was its recognition of the Indians’ right to the permanent possession of their land. But working out exactly which land was theirs, and disentangling competing claims, proved to be a complex and slow business, with the official demarcation of indigenous boundaries still progressing almost 30 years after the new Constitution became law.

Now that process — far from complete — has been halted by the Temer administration and Brazil’s Congress, which are openly hostile to the idea of recognizing more indigenous land.

This of course has major repercussions for Indians whose land claims have yet to be settled. It means, for example, that there is virtually no chance at the moment of ending what a mission of the European Parliament has called “the genocide of the Guarani Kaiowá people.” Every time these Indians try to reoccupy their traditional land — which happens to lie beside federal roads — they face threats from private militias employed by agribusiness. The Guarani Kaiowá have been tortured and assassinated, and suffer from high rates of malnutrition, alcoholism and suicide.

Few advances under Lula

Like social movements throughout Brazil, indigenous people placed high hopes in President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who in 2002 became the first person raised in the working class to ever be elected to the country’s highest office.

But Lula did not live up to these expectations. His social policies, widely praised for tackling the country’s historic problem of profound social inequality, were directed mainly to the poor living on the outskirts of large cities. The difficulties faced by indigenous and traditional communities were never a priority for Lula.

The leader Gersem Baniwa, from the Baniwa ethnic group in the state of Amazonas, summarized well what many Indians felt at the time:

After two decades of intense struggle by the Brazilian indigenous movement and a historic political conquest by the Workers’ Party, and Lula… it would be a pleasure to be able to talk about the historical gains… made in the field of indigenous peoples’ rights. But unfortunately, this is not the feeling that prevails among indigenous peoples. Instead, they feel disappointment and doubts. The state of mind is not worse because, thanks to recent advances, indigenous people no longer put their hope in a party or a “savior of the country,” but in their own strength and capacity for resistance, mobilization and struggle.

Lula’s two presidential terms saw only 81 new indigenous territories created — a significant drop compared with the 118 designated during the two terms of predecessor, Fernando Henrique Cardoso (FHC), a president whom the Indians had not regarded as an ally. In part, Lula’s poor performance was justifiable, as FHC had dealt with the uncontroversial indigenous territory designations, leaving his successor to handle the more complex and problematic cases, which often involved serious conflicts.

Dilma fails to deliver

Indigenous relations only worsened under President Dilma Rousseff who took office in 2011. “There was a real rupture in Indian policy from the Lula to the Dilma governments,” said Márcio Santilli, a founding member of the Socioenvironmental Institute (ISA) and a former president of the government’s indigenous agency, FUNAI.

During Dilma’s time in office, only 26 indigenous territories were created, a poor showing that would have been worse if she hadn’t rapidly signed decrees establishing reserves during the final days of her government, when she knew her impeachment was imminent.

Dilma’s indigenous-unfriendly policies were the result of “the radical expression of an almost desperate strategy to promote economic growth at any price,” Santilli explained. “As well as reducing dramatically the rate at which indigenous territories were established, her government largely kept temporary presidents at the head of FUNAI, and cut the agency’s budget. [Dilma] also reduced the rate at which land titles were given to quilombolas [areas occupied by runaway slaves] and at which conservation units and agrarian reform settlements were created.”

All this showed, Santilli concluded, that her government was reluctant to conserve land for social and environmental purposes, and instead, supported largely unregulated economic development in Amazonia.

Dilma’s main vehicle for unleashing economic progress was her Growth Acceleration Program (PAC), an ambitious government program, first announced by Lula, then expanded greatly during her government. PAC resulted in huge investments in highways, energy and water resource projects — all with a view to increasing exports and promoting unregulated economic growth.

Cleber César Buzatto, executive director of the Missionary Indigenous Council (CIMI), an important Catholic institution that has been working with Brazilian Indians since 1972, said that Dilma subordinated the rights of indigenous peoples to the demands of the PAC: “A prime example of this was the construction of the Belo Monte hydroelectric power plant on the Xingu River in the state of Pará,” he said.

The indigenous impacts of the Belo Monte hydroelectric dam — one of the biggest in the world — were so severe that in 2015 Thais Santi, the prosecutor for the independent Federal Public Ministry (MPF) in Altamira, told Mongabay: “There is a process of ethnic extermination underway in Belo Monte by which the federal government continues with the old colonial practice of integrating the Indians into the hegemonic society.”

The MPF is currently suing the Brazilian federal government and construction company, Norte Energia, for the crime of ethnocide against Xingu River indigenous communities.

FUNAI’s failures

The anthropologist Márcio Meira was president of FUNAI from 2007 to 2012, when the agency adopted a raft of policies that enraged indigenous groups. These included agreeing to the licensing of Belo Monte, as well as other hydroelectric dams, such as the Teles Pires and São Manoel projects in the Tapajós river basin, along with a controversial restructuring of FUNAI itself.

Meira said later that he was aware at the time of the emergence of formidable new anti-indigenous forces: “When I was president of FUNAI, it was clear to me that an anti-indigenous wave was gathering force in Brazilian society, mainly due to the power of the heirs of the old agrarian elites, who were launching an attack on land in the north and northwest of the country.”

According to Meira, seismic shifts in the national economy fuelled hostility to indigenous land claims: “There has been a decline in industrial output, while agricultural production and agricultural exports have increased,” he explained. “The Brazilian economy has become increasingly dependent on agribusiness and this has had political repercussions. It is not a question of people being against the Indians because they are Indians or even because they have too much land. The problem is that the Indians have lands these political actors want.”

The ascendant bancada ruralista, Brazil’s agribusiness lobby, has long eyed indigenous reserves and other conserved Amazon lands hungrily. Under Dilma, the lobby’s power and influence grew.

In a June 2013 press release, National Congress Senator Kátia Abreu claimed that activists had seized control of FUNAI and were causing trouble: “Ideological militants inside FUNAI, linked to CIMI and national and foreign NGOs, are encouraging the Indians to invade productive lands,” she accused.

Sen. Abreu, also president of the Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock (CNA), and later to be Dilma’s Agriculture Minister, went on to say that: “The CNA supports the idea of adopting a new indigenous policy, in which decisions are taken, not only by FUNAI, but with the participation of other ministries and federal government bodies. It is unacceptable that a question as important as [indigenous territory designation] is in the hands of a single body, staffed by ideological militants who are not furthering the national interest.”

This strongly worded challenge — only a proposal in 2013 — is becoming reality today.

Anti-indigenous land offensive intensifies

Michel Temer received crucial support from the bancada ruralista in his controversial bid for power, which succeeded on a temporary basis in April 2016 and became permanent in August. From the beginning, he made it clear that as President he would reverse the indigenous land measures that the Justice Minister and FUNAI president had rushed through during the last months of Dilma’s administration. He also promised the bancada ruralista that he would rollback indigenous rights. But, with indigenous groups and their supporters geared to damage control, Temer hasn’t yet achieved all his goals.

At the end of 2016, with the government reeling from corruption accusations, it still found time to issue new draft regulations changing the administrative procedure for marking out indigenous land. Indians and NGOs linked to the indigenous movement reacted angrily, calling the plan “an unprecedented aberration” that would make it impossible for the state to carry out its “constitutional obligation” to give Indians the right to possess their land.

The reaction was so strong that the proposal had to be to be withdrawn. but on 18 January 2017 the Justice Ministry issued Ministerial Order 68, another attempt to push through the same changes. Once again, the reaction was fierce and just a few hours after Temer openly supported the new order, it was revoked.

But that wasn’t the end. Soon after, the Justice Ministry published

Ministerial Order 80, a watered-down version of the earlier proposal. Even so, it contained an important change in the way indigenous lands are recognized, creating a Specialized Technical Group to do the job.

Previous to Ministerial Order 80, indigenous lands were recognized and borders established through a technical process carried out by experts, including anthropologists, within FUNAI. But Order 80 brings new bodies into the decision-making process, including some known to be hostile to the Indians, along with professionals with no specialist indigenous knowledge. According to Juliana de Paula Batista, an ISA lawyer, the government’s intention was to “interfere politically in technical studies.”

Indigenous groups worry that Temer has more draconian plans. Federal deputy Osmar Serraglio, a hard-line politician, has long campaigned for curtailing the constitutional rights of Indians, traditional communities and quilombolas. He has repeatedly said that no more land should be given to Indians, because “land doesn’t fill stomachs.” In other words, Indians are a welfare problem, which should be resolved through federal hand-outs of food, but they shouldn’t be entrusted with land.

In February 2017, Temer put Serraglio at the head of the Justice Ministry, to which FUNAI is subordinated. From the indigenous perspective, the fox now runs the henhouse.

Mongabay requested interviews with the Justice Minister, the current president of FUNAI and members of the bancada ruralista but none agreed to comment.

Prospects

The government offensive to limit indigenous rights is gaining momentum. In March 2017, Temer restructured FUNAI, abolishing 87 of the 770 primary managerial positions in the agency, and creating new barriers for appointing replacement staff. The personnel most affected by these cuts dealt with the demarcation of indigenous land and the provision of environmental licenses for infrastructure projects such as dams. Antônio Fernandes Toninho Costa, the current FUNAI President, was not consulted In the restructuring.

Marcio Santilli was outraged: “The government and Congress are rotten and the rights of the whole population, including Indians and traditional populations, are threatened.” From Santilli’s perspective the one bright light is that the indigenous movement is resisting courageously and has not been co-opted by Temer’s government.

Indeed, despite recent gains, agribusiness isn’t having it all its own way: it and the government have been rocked by recent scandals and plagued by infighting. Not long after Serraglio’s appointment as Justice Minister, for example, a federal police operation, code named Carne Fraca (Weak Meat), revealed a large-scale criminal scheme in which inspectors and slaughterhouses colluded to circumvent the country’s public health controls. China and other buyers of Brazilian meat banned shipments. Serraglio’s name was mentioned in the evidence. JBS, the world’s biggest meatpacking company, which is one of the companies under investigation, was the biggest funder of Serraglio’s electoral campaign in 2014.

“Those behind the anti-indigenous offensive will find growing resistance both from Indians and from other sectors of society,” concluded Santilli.

That movement plans a major show of strength with an event on 24-28 April. The initiative, called the Acampamento Terra Livre (Free Land Camp), will bring together 1,500 indigenous leaders from across the nation. They’ll set up camp in Brasilia, host marches, debates, protests and cultural events. The indigenous leaders will also seek meetings with the executive, legislative and judiciary branches of the government. The aim is “to unify struggles in defense of the Indian people.”

With Brazil still in its worst economic recession ever, the Temer government wracked by scandal and its popularity as low as Dilma’s the month she was impeached (Temer now has a 73 percent disapproval rate) — the Free Land Camp could make a significant impact.

The key role indigenous communities play in Amazon rainforest protection, combined with the significant carbon sequestration those forests provide, means that the outcome of the current land rights battle matters greatly, not just for indigenous groups, or even for Brazil, but to the whole world.

(Leia essa matéria em português no The Intercept Brasil. You can also read Mongabay’s series on the Tapajós Basin in Portuguese at The Intercept Brasil)

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.